Imagine this:

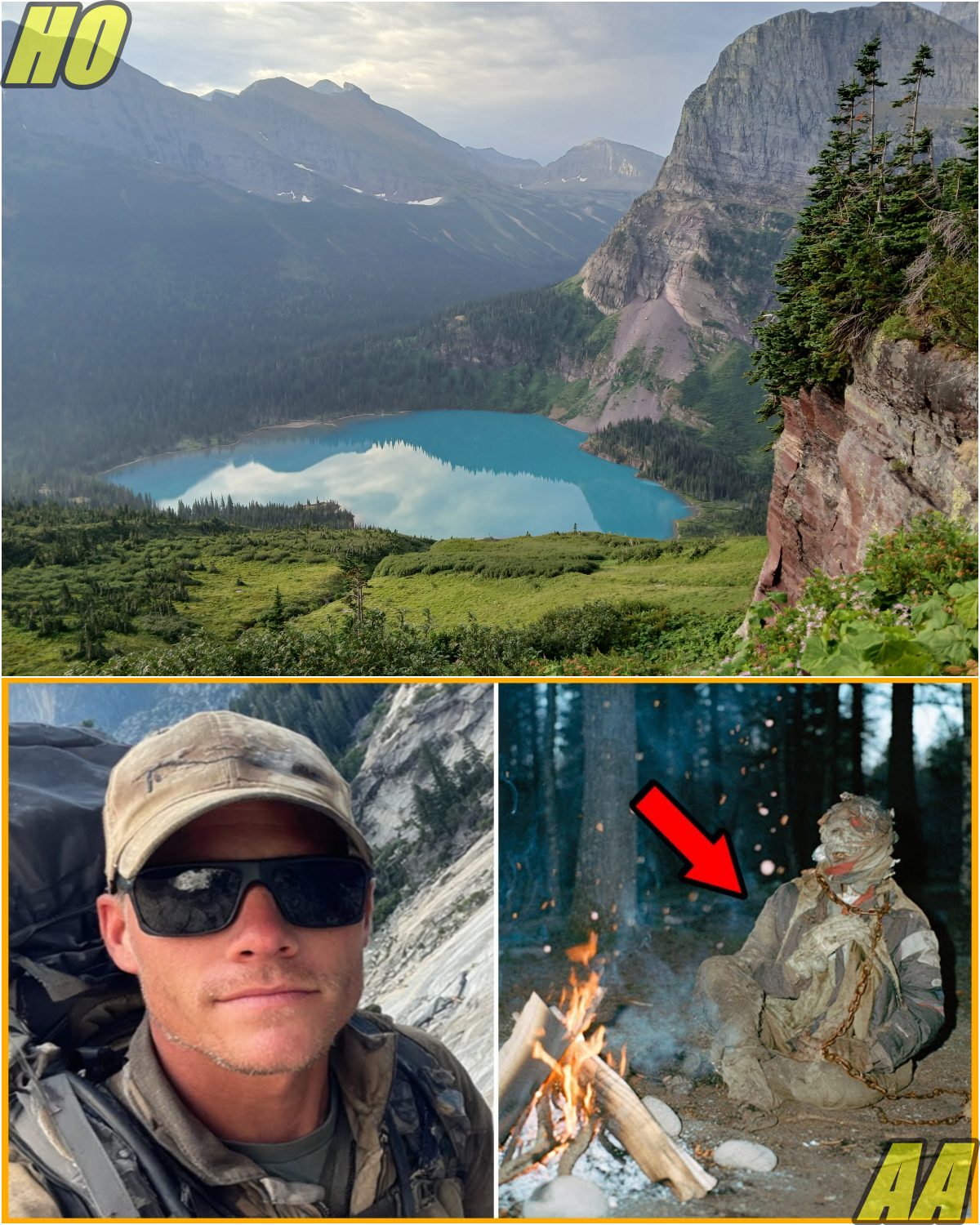

You’re hiking through the silent wilderness of Glacier National Park, Montana. The air is thin, the forest ancient, and the only sound is the crunch of your boots on pine needles. Suddenly, you notice a figure sitting by an old campfire, motionless, a thermos in his hands. At first, he looks like any tired hiker—until you call out and get no response.

You approach, and horror grips you. He’s not asleep. He’s dead.

But the true terror comes later, when forensic experts reveal he’s been dead for three years, his body mummified by the cold, dry mountain air, waiting to be discovered.

This is the story of Mark Wells, whose disappearance and grim discovery still haunt everyone who hears about it.

The Beginning

Mark Wells grew up in Denver, Colorado, the only child of a quiet, middle-class family. His father was a schoolteacher, his mother ran a small accounting firm. From childhood, Mark loved hiking and mountaineering, joining clubs and learning survival skills. By his mid-thirties, he was an experienced outdoorsman, cautious and methodical—never reckless, always prepared.

In September 2014, Mark took a week off work, seeking escape from the noise and pressure of city life. He dreamed of a place with no cell reception, no emails, just stars and silence. Glacier National Park was his choice—a vast, rugged expanse of mountains, lakes, and forests, far from civilization.

Mark planned a four-day hike along the Huckleberry Lookout Trail. He left a detailed route with his parents, packed extra food, a satellite phone, and emergency gear. On September 9th, surveillance cameras recorded him arriving at the trailhead, calm and organized, dressed in an orange jacket and trekking pants, his heavy backpack slung over his shoulder.

He vanished into the trees.

He never came back.

The Search

Mark was supposed to return by September 12th, and call his parents that evening. When no call came, his worried mother contacted the National Park Office. Rangers took the report seriously—Glacier Park is beautiful, but deadly, with bears, mountain lions, sudden weather changes, and treacherous cliffs.

Ranger Jacob Harrison led the search. Mark’s car was still at the parking lot, locked and undisturbed. Search dogs traced his scent along the trail, but lost it where an animal path branched off. Helicopters swept the area, searching for the bright orange of his jacket, but found nothing. Volunteers combed the forest, checked campsites, rivers, and canyons. Divers searched lakes. No sign of Mark.

His parents flew in from Denver, refusing to give up hope. They hired private investigators, put out ads, and offered rewards. But as months passed, the trail grew cold. Mark’s case was classified as missing.

Two years passed. Silence.

The Discovery

August 2017 brought an unusual heatwave and forest fires to Montana. Glacier Park was closed to most visitors, but a group of mountain bikers received special permission to ride a remote trail.

Thomas Kendrick, his wife Sarah, and their friends Michael and Jennifer Rogers were halfway through their route when they stopped to fix a flat tire. Thomas wandered down a small path and stumbled into a clearing—a circle of stones marking an old campfire, long abandoned.

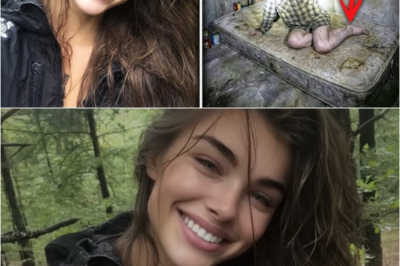

And there, leaning against a tree, sat a man with a thermos in his hands, head bowed, legs stretched out.

He looked as if he’d simply dozed off after a long hike.

Thomas called out. No response. He approached, and the nightmare revealed itself. The man’s skin was dark and taut, his eyes sunken, his fingers twisted around the thermos. He was a mummy, preserved by the cold, dry mountain air.

The bikers called the rangers, who arrived within hours. The body was sitting upright, calm and organized—unusual for a victim of hypothermia. There were no belongings except the thermos. But the worst was yet to come.

The Investigation

Forensic experts cordoned off the clearing and examined the scene. When they moved the body, they discovered deep marks on the wrists and ankles—old bruises, the kind left by shackles or chains. The tree behind the body bore scars from a metal cable, worn smooth by years of friction.

Nearby, they found a steel cable noose and a two-meter chain welded to a lock, which had been attached to the tree. Mark Wells had been chained there, unable to escape, limited to a two-meter range.

Further examination revealed a primitive camp: a flattened patch where a tent once stood, rusted cans buried in the ground, a faded water bottle, and a metal carabiner. Ten meters away, another chain was attached to a tree, ending in a collar—empty, but the bark showed it had been used for a long time.

Dental records confirmed the mummy was Mark Wells. His parents were notified. The orange jacket, boots, and thermos were his. Medical examination revealed death by dehydration and exhaustion—no food in his stomach, no water, organs ravaged by starvation. He had survived up to ten days, trying desperately to free himself, his wrists and ankles raw and infected.

Mark had died slowly, chained to a tree, alone in the wilderness.

The Questions

Detective Linda Macdonald, a veteran of the serious crimes division, led the investigation. The case was classified as murder.

But why Mark? He had no enemies, no debts, no criminal past. His life was ordinary—work, hiking, home.

Was it a random attack? A maniac in the woods? But there were no other victims in Glacier Park, no history of kidnapping or murder.

Had Mark stumbled upon a crime? A poacher’s camp? The second chain suggested another victim—or perhaps an animal, kept by someone for illegal purposes.

The poacher theory fell apart. Why keep a bear or wolf so far from the road, and why leave a witness to die so slowly? The evidence pointed to something darker—a sadist who wanted to watch his victim suffer.

Months passed. Hundreds of interviews, thousands of documents, and no answers.

The Second Body

Then, in early 2018, Detective Macdonald received an anonymous letter.

“He wasn’t alone. Look north of the clearing. There is another victim there.”

A search team with dogs and metal detectors combed the area. 800 meters north of Mark’s clearing, they found a shallow grave—a skeleton, broken ribs, a cracked skull. Among the remains was a passport: Emily Russell, 27, from Portland, Oregon, missing since July 2014.

Emily had disappeared two months before Mark. She was a hiker, depressed after a breakup, seeking solace in the mountains. But she vanished in Oregon, not Montana. There was no record of her entering Glacier Park. Had she been brought there against her will?

The Killer

Forensic analysis of the anonymous letter revealed a partial fingerprint—David Harp, a 51-year-old ex-soldier with PTSD, living in Callispel. Neighbors described him as withdrawn, troubled, haunted by his time in Afghanistan.

Detectives searched Harp’s apartment, finding keys matching the chains, maps of Glacier Park with the clearing marked, and a bloodstained backpack.

Under interrogation, Harp confessed.

He hadn’t killed Mark or Emily directly—he’d left them chained in the clearing, letting nature do the rest.

Harp described his descent into madness. After the army, he couldn’t adjust to civilian life. He built a camp in Glacier Park, seeking isolation. In summer 2014, Emily wandered into his camp and startled him. In a rage, he struck her, killing her accidentally. He buried her body, but something inside him broke.

When Mark stumbled into the camp two months later, Harp forced him at gunpoint to the clearing, chained him to the tree, and watched him die slowly. It was an experiment, a twisted assertion of control.

Aftermath

David Harp was charged with two counts of first-degree murder. The defense argued insanity, but the jury found him guilty. He received two life sentences without parole.

Mark’s parents attended the sentencing, hollowed by grief but grateful for justice. Emily’s family finally received answers, however terrible.

Epilogue

The clearing in Glacier Park became a dark landmark, a reminder of how thin the line between civilization and wilderness, between sanity and madness, truly is.

Mark Wells was an experienced, cautious hiker. Emily Russell was simply lost. Both fell victim not to nature, but to a man broken by his own demons.

Sometimes, the greatest danger in the wild is not the bears, cliffs, or storms—it’s the darkness that lurks in the human mind.

Their story remains a haunting lesson: nature is beautiful, but it does not forgive mistakes. And sometimes, the most dangerous thing in the wilderness is another person.

News

S – Model Vanished in LA — THIS Was Found Inside a U-Haul Box in a Storage Unit, WRAPPED IN BUBBLE WRAP

Model Vanished in LA — THIS Was Found Inside a U-Haul Box in a Storage Unit, WRAPPED IN BUBBLE WRAP…

S – Girl Vanished on Appalachian Trail — Found in Underground Bunker, BUT SHE REFUSED to Leave…

Girl Vanished on Appalachian Trail — Found in Underground Bunker, BUT SHE REFUSED to Leave… On May 12th, 2020, Alexia…

S – Detective Found Missing Woman Alive After 17 Years in Basement—She Revealed 13 More “Lab Rats”

Detective Found Missing Woman Alive After 17 Years in Basement—She Revealed 13 More “Lab Rats” Atlanta, January 10th, 2015. Detective…

S – A Retired Detective at a Gala Spotted a Wax Figure That Matched His 21-Year Unsolved Case

A Retired Detective at a Gala Spotted a Wax Figure That Matched His 21-Year Unsolved Case Charleston, South Carolina. October…

S – Tragic message discovered as married couple disappeared after being left behind while diving

Tom and Eileen Lonergan were never found after they were unknowingly left at sea, 60km from the Australian coast A…

S – SWAT Officer Vanished in 1987 – 17 Years Later, a Garbage Man Uncovers a Chilling Secret

SWAT Officer Vanished in 1987 – 17 Years Later, a Garbage Man Uncovers a Chilling Secret In the summer of…

End of content

No more pages to load