Antique Shop Sold a “Life-Size Doll” for $2 Million — Buyer’s Appraisal Uncovered the Horror

March 2020.

Marcus Chen was no stranger to rare treasures. His Manhattan penthouse was a museum of centuries-old paintings, ancient sculptures, and artifacts from every corner of the world. But nothing had ever captivated him like the piece Bernard Whitmore showed him that cold afternoon—a life-size Victorian doll, hauntingly beautiful, perfectly preserved.

The doll, dressed in a deep burgundy silk gown, stood behind glass in Whitmore’s secretive Upper East Side shop. Its eyes—hand-blown glass—seemed almost alive. The skin, waxy yet textured, the hair unmistakably human. Every detail, down to the freckles on the nose, was so flawless it bordered on unsettling.

Whitmore whispered, “Late 1860s. European craftsmanship. Possibly French. The provenance is mysterious, but the artistry is unmatched.”

Marcus, entranced, didn’t hesitate. Two million dollars exchanged hands, and the “doll” was installed in his private gallery.

The Uneasy Collector

For weeks, Marcus couldn’t stop staring at the figure. There was something ineffably sad about its expression, something that made him feel less like a collector and more like a rescuer. He researched Victorian mourning rituals, memento mori traditions, anything that might explain the origins of his new prize. But the more he learned, the more questions he had.

By late April, with the world locked down, Marcus hired Dr. Sarah Williams—a forensic art expert with a background in anthropology—to appraise the piece for insurance. Sarah’s reaction was immediate and visceral.

“My god,” she whispered, eyes wide as she examined the doll. But soon, her awe shifted to concern. She spent hours photographing, measuring, and inspecting. The details were too perfect: the pores, the fingernails, the subtle bone structure beneath the skin.

Sarah finally said, “I need a CT scan. Something about this isn’t right.”

Revelation in the Machine

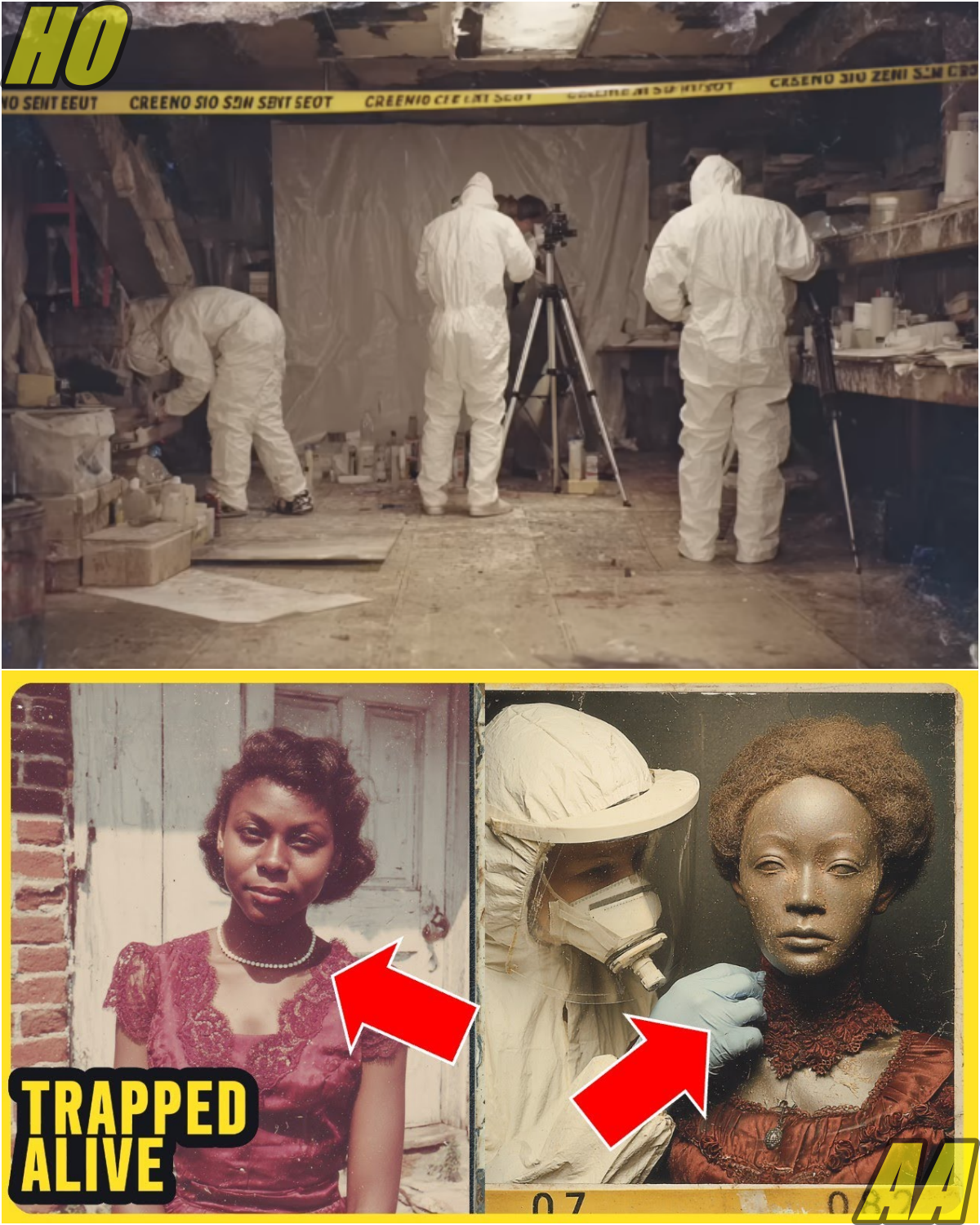

The scan was arranged at a private lab. As the images appeared, the technician frowned. “There’s bone density here. And… organs. This isn’t a doll.”

Sarah’s face drained of color. “Marcus, this is a human body.”

Police were called. The penthouse became a crime scene. The “doll” was transported to the medical examiner’s office, and Marcus was left reeling—his prized purchase now the center of a murder investigation.

A 57-Year-Old Secret

Detective James Porter took the case. The documentation traced the piece back to a French estate in 1870, but the trail quickly grew cold. Whitmore, the dealer, had purchased it from a Connecticut estate sale, which led to a Boston dealer, which led to nowhere. Each previous owner was dead or unreachable.

The medical examiner made a chilling discovery: the body belonged to a black teenage girl, approximately 16–18 years old, preserved using chemicals and resin. Carbon dating of the dress placed her death between 1955 and 1965. But DNA was degraded—identification impossible.

Porter pulled hundreds of missing persons reports from that era. Most were dismissed as runaways, barely investigated. The victim’s identity remained a mystery.

The Civil Rights Connection

A breakthrough came from Dr. Jennifer Martinez, a researcher compiling oral histories of missing persons from the civil rights era. She cross-referenced Porter’s data and found three cases that stood out—all black teenage girls, all disappeared in the summer of 1963, all civil rights activists.

But one matched best: Diana Maxwell, 17, Birmingham, Alabama. Her sister, Ruth Maxwell Johnson, still lived in Atlanta, still searching for Diana after 57 years.

Porter, Sarah, and Marcus flew to Atlanta. Ruth confirmed the dress—Diana’s favorite. She provided a DNA sample, and shared the heartbreaking story: Diana was in love with Thomas Richter Jr., the son of a powerful, segregationist family. The night she disappeared, she was supposed to meet Tommy to confront his father.

Ruth revealed Diana’s diary—entries about their secret romance, plans to escape north, and the hope that love could conquer hate.

Uncovering the Past

Porter investigated the Richter family. Thomas Sr. was long dead, with rumored ties to the Klan. Tommy died in 1995, officially suicide. The only living witness, a former housekeeper, recalled a night in July 1963 when Diana visited the Richter home. She never saw Diana leave.

The preservation technique pointed to Dr. Wilhelm Castner, a German taxidermist in New Orleans, known for lifelike work and rumored to accept private commissions. But Castner was dead, and records were lost. Another dead end.

DNA and Closure

Months passed. The lab finally produced partial DNA markers—an 85–90% probability the remains were Diana’s. Not absolute, but enough for Ruth.

“I want to bring my sister home,” Ruth said. Diana’s remains were released for burial. The funeral in Birmingham drew activists, journalists, and strangers moved by the story. Ruth’s eulogy: “My sister died because she believed in love and equality. Her story was buried, but now it’s told.”

Justice Denied, Truth Revealed

The investigation stalled. The suspects were dead, the records incomplete. Officially, the case was closed—a cold case homicide, no leads, no suspects.

But Porter, Sarah, Marcus, and Ruth refused to let Diana’s story fade. They published her story, advocated for new protocols in museums and collections, and continued searching for other victims. Sarah uncovered three more possible cases—other “dolls” that might be hidden in private collections.

Ruth, now 74, vowed to keep searching. “Diana waited 57 years to come home. If there are others, they deserve the same chance.”

Legacy

Diana Maxwell’s grave is now a place of remembrance, not just for her, but for countless others whose stories were buried by prejudice and indifference. Her voice was silenced, but her story lives on—a testament to the power of bearing witness, of refusing to let injustice remain hidden.

Justice was never served. But truth, finally, was told.

If you were moved by Diana’s story, share it. Demand accountability. Ask museums and collectors to verify their artifacts. Let the lost be found, and the silenced be named.

News

S – Model Vanished in LA — THIS Was Found Inside a U-Haul Box in a Storage Unit, WRAPPED IN BUBBLE WRAP

Model Vanished in LA — THIS Was Found Inside a U-Haul Box in a Storage Unit, WRAPPED IN BUBBLE WRAP…

S – Girl Vanished on Appalachian Trail — Found in Underground Bunker, BUT SHE REFUSED to Leave…

Girl Vanished on Appalachian Trail — Found in Underground Bunker, BUT SHE REFUSED to Leave… On May 12th, 2020, Alexia…

S – Detective Found Missing Woman Alive After 17 Years in Basement—She Revealed 13 More “Lab Rats”

Detective Found Missing Woman Alive After 17 Years in Basement—She Revealed 13 More “Lab Rats” Atlanta, January 10th, 2015. Detective…

S – A Retired Detective at a Gala Spotted a Wax Figure That Matched His 21-Year Unsolved Case

A Retired Detective at a Gala Spotted a Wax Figure That Matched His 21-Year Unsolved Case Charleston, South Carolina. October…

S – Tragic message discovered as married couple disappeared after being left behind while diving

Tom and Eileen Lonergan were never found after they were unknowingly left at sea, 60km from the Australian coast A…

S – SWAT Officer Vanished in 1987 – 17 Years Later, a Garbage Man Uncovers a Chilling Secret

SWAT Officer Vanished in 1987 – 17 Years Later, a Garbage Man Uncovers a Chilling Secret In the summer of…

End of content

No more pages to load