They Opened Fred Rogers Locked Drawer, The Letter Inside Is Chilling | HO

The Man Who Made the World Feel Safe

For more than three decades, Fred Rogers—the soft-spoken man in cardigans and sneakers—welcomed millions of children into Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. His voice was calm, his smile unwavering. He made generations of kids believe the world was kind and safe.

But behind the warmth and music, Rogers carried a private darkness.

When he died in 2003, his wife Joanne Rogers revealed that her husband had kept a locked drawer in his study—a drawer she had promised never to open while he was alive.

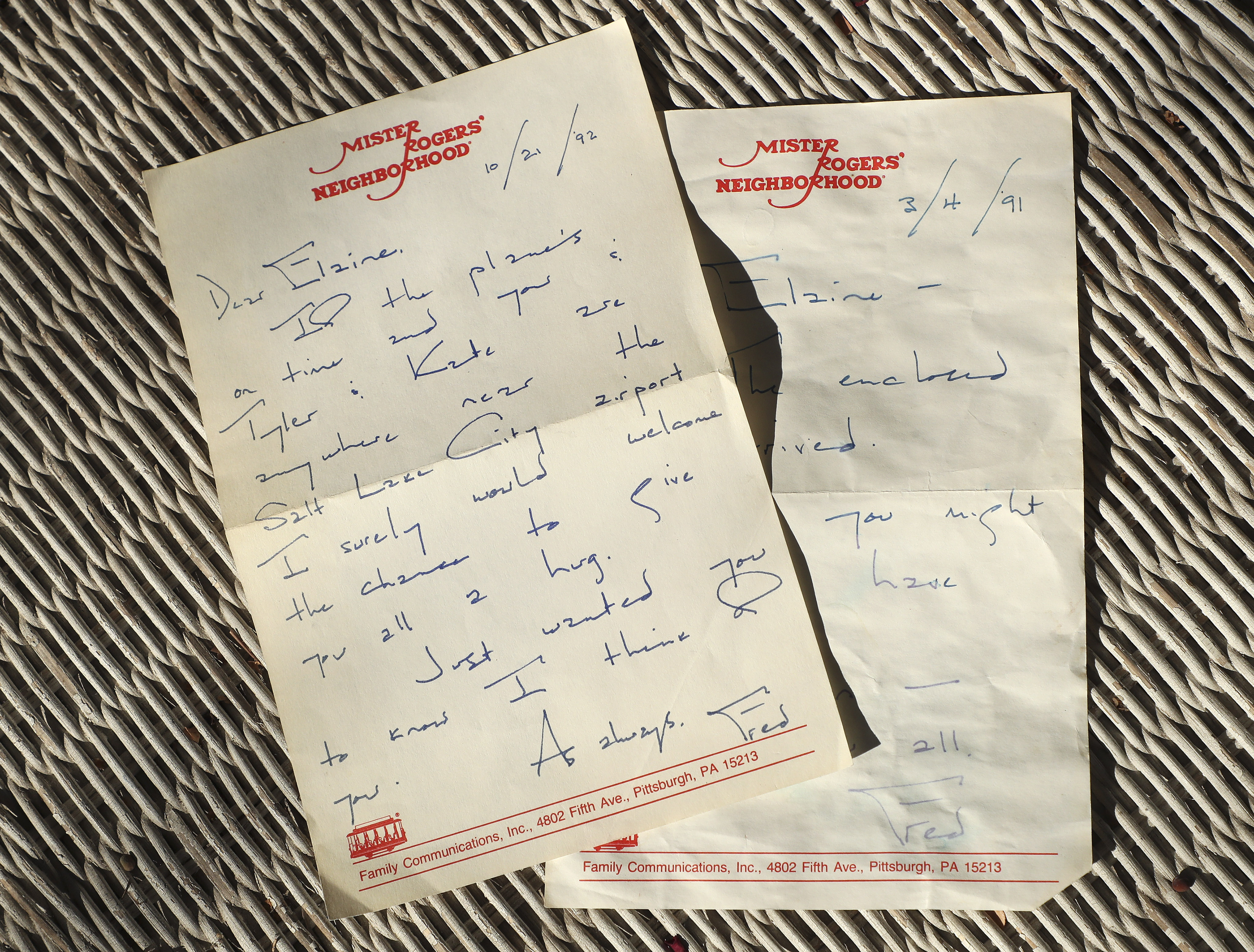

Inside, archivists would find a stack of letters written over 30 years. Letters Fred had addressed to someone he never met, yet spoke to every day.

They were addressed to God.

The Letters No One Was Meant to See

Every March 20th—his birthday—Fred sat alone at his desk and wrote one letter. He never showed them to anyone. Not his wife, not his producers, not his pastor.

In those letters, he didn’t sound like the confident man who sang about self-worth and kindness. He sounded haunted.

“I try to help them, Lord,” one letter began, dated 1978. “But sometimes I fear I’m failing. I can teach them to love others. But who teaches me?”

Rogers questioned whether his life’s work—hundreds of hours of children’s television—was enough. He asked if he had done more harm than good by showing the world a man who never seemed to struggle.

And yet he did struggle—deeply.

Because beneath the gentle neighbor lived a boy who had once been sick, lonely, and afraid of the dark.

The Boy Who Watched from the Window

Fred Rogers was born in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in 1928, the son of a wealthy steel executive and a banker’s daughter. His father built a mansion with heated floors and a private elevator. His mother filled it with servants and silence.

He was a shy, isolated child who spent most of his time indoors, too sickly to play outside. At two years old, he nearly died from a combination of measles and scarlet fever. He spent forty-seven days confined to bed, hallucinating from high fever.

His mother, Nancy, sat by his side, playing piano melodies on the black keys—notes easier for his frail fingers to reach. She told him that each black key was a feeling.

That piano became his first friend.

But the world outside the estate was cruel. At school, Fred’s high-pitched voice made him a target. Classmates called him “sissy.” They shoved him into lockers. Once, they poured chocolate milk over his sheet music.

He never forgot the humiliation. Years later, he said, “I made a promise when I was bullied that if I ever had power, I’d never use it to make anyone feel small.”

The Ghosts of Latrobe

Even as a child, Fred was drawn to sorrow. At age six, he stood at the window of his family home and watched rescue crews pull bodies from a train derailment just down the tracks. Forty-seven people died.

That night, he asked his mother, “Why do people get hurt when they’re just trying to go somewhere?”

It was a question that would shape his life’s mission—and fill the pages of those secret letters.

“I still wonder,” he wrote decades later. “How many children ask that and never get an answer?”

From Puppets to Purpose

Fred’s mother encouraged him to channel his emotions into creativity. She gave him a set of sock puppets and a homemade puppet stage. One of those characters, Daniel the Tiger, became his lifelong alter ego—a stand-in for all the emotions he couldn’t express.

As he grew, he found music—his second language. He composed his first full piece, Melody for String Quartet in D minor, at age fifteen. His classmates mocked it as “funeral music.”

Fred didn’t fight back. He wrote in his journal that night:

“I think the sad songs understand me best.”

He would later tell children, “There’s no such thing as someone who doesn’t matter.” But he wrote those words for himself first.

The Hidden Anger

Rogers’ public calm was born not of peace, but of discipline.

In his twenties, during seminary training, he confessed to struggling with rage—not toward others, but toward himself. “I used to dream of fighting back,” he admitted in an unpublished 1986 manuscript titled The World of Mr. Rogers.

That manuscript, discovered beside the letters after his death, revealed a side of him no one had seen: his anger, his self-doubt, his guilt.

He wrote about smashing a puppet during an argument with Joanne in 1956—something that haunted him for years. “I destroyed something innocent,” he wrote, “because I couldn’t destroy my own pain.”

From that moment on, he vowed to transform anger into empathy. Decades later, he would turn that memory into a song that became one of his most powerful lessons:

What do you do with the mad that you feel?

The 1986 Manuscript They Refused to Print

Rogers’ 1986 manuscript was so personal that publishers refused it.

In one chapter, he revealed that as a teenager he had suffered from severe cystic acne, leaving deep scars on his face. He confessed to spending hours before the mirror applying makeup to hide them—long before he was on television.

“I used to think I was too ugly to be kind,” he wrote. “So I learned to make others feel beautiful.”

He admitted he chose television over ministry because he feared people would judge his face. On screen, he could control the frame, the light, the distance.

He even shared that sometimes, during emotional scenes, he would subtly wipe away his makeup mid-filming—so children could see him as imperfect and real.

That honesty scared publishers. They called it “too raw for his image.” The manuscript stayed locked away—right beside the letters to God.

The Letter That Broke His Faith

Among the final letters, dated 1999, was one unlike the rest.

Rogers was dying of stomach cancer, though he hid it from the public. His handwriting was weak, his sentences fragmented.

“Dear Lord,” it read,

“I’m not afraid to die. I’m afraid of not finishing what You gave me. The children… they still need to know it’s okay to be sad. I tried to show them. Did I do enough?”

He signed it simply, Fred.

When Joanne read it after his death, she wept. “He doubted himself more than anyone knew,” she later said. “He didn’t think he had done enough good in the world.”

The Secret of 143

For decades, Fred maintained his weight at exactly 143 pounds.

To most people, it was just a number. But in his letters, he revealed the hidden meaning: 1-4-3. I love you.

He wrote,

“If I can stay at 143, then I know I’m living the message. Body, spirit, and purpose in harmony.”

He weighed himself every morning, prayed for every name on his list of 500 children, and swam three miles in the early dawn. His discipline wasn’t vanity—it was ritual, a quiet act of devotion.

The Man Who Wrote Back

During his 33-year television career, Fred personally responded to thousands of letters from children.

One note from a six-year-old girl who lost her dog read, “Will God take care of him?”

Fred replied, “Yes, and God will take care of you too.”

What viewers didn’t know was that each time he wrote one of those replies, he kept a copy—and later placed it in his drawer beside his own letters to God.

“If He reads mine,” Rogers wrote, “perhaps He’ll read theirs, too.”

The Drawer Opens

After Fred’s death in 2003, Joanne waited nearly five years before opening the drawer. Inside were thirty-three letters to God, the unpublished manuscript, and a photograph of a piano—the same one his mother had taught him to play on during his childhood fevers.

Archivists who examined the documents described them as “achingly human.”

“He wasn’t a saint,” one researcher said. “He was a man who wrestled with darkness every day—and chose gentleness anyway.”

The Final Goodbye

In his final months, Fred could barely walk. The cancer had spread, and he used a walker behind the scenes. But he refused to let children see him weak.

In August 2001, he recorded his final message to the Neighborhood—a quiet farewell to the red trolley that had carried him through generations of childhoods.

He looked into the camera and said, softly,

“You were special to me.”

He was speaking to the trolley. But also, perhaps, to the millions who grew up believing he would always be there.

The Letter Inside the Drawer

The last page in Fred Rogers’ drawer was dated February 20th, 2003—one week before he died. It was written in a shaky hand.

“Dear Lord,

The work is done. The songs are sung. The Neighborhood is asleep.

I hope I was kind enough.

Please, take care of the children who wake in the dark.

And if you see Daniel, tell him I’ll be home soon.”

When archivists finished reading it aloud, the room was silent.

Fred Rogers had spent his entire life teaching others how to talk about fear, loneliness, and love. But in the end, the person he most needed to comfort was himself.

And in that final letter—his last broadcast to heaven—he did.

The Legacy That Whispers Still

Two decades later, the Fred Rogers Archive in Pittsburgh holds over 22,000 items: his puppets, his scripts, his red cardigan. But the most haunting artifact is still that drawer—his letters to God, now sealed behind glass.

Visitors often pause longest at the final note, written in fading ink.

“Please, take care of the children who wake in the dark.”

It’s the line that proves Fred Rogers’ greatest secret: he wasn’t just talking to the children who watched him. He was talking to the frightened boy he used to be.

And perhaps—to all of us.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load