The Widow Who Took Her Slave’s Husband as Her Own: Georgia’s Unforgiven Secret of 1839 | HO

A Case Buried for More Than a Century

Welcome to this journey through one of the darkest and most disturbing cases in Georgia’s hidden history — a story once stricken from the record, sealed behind polite silence, and nearly erased from collective memory.

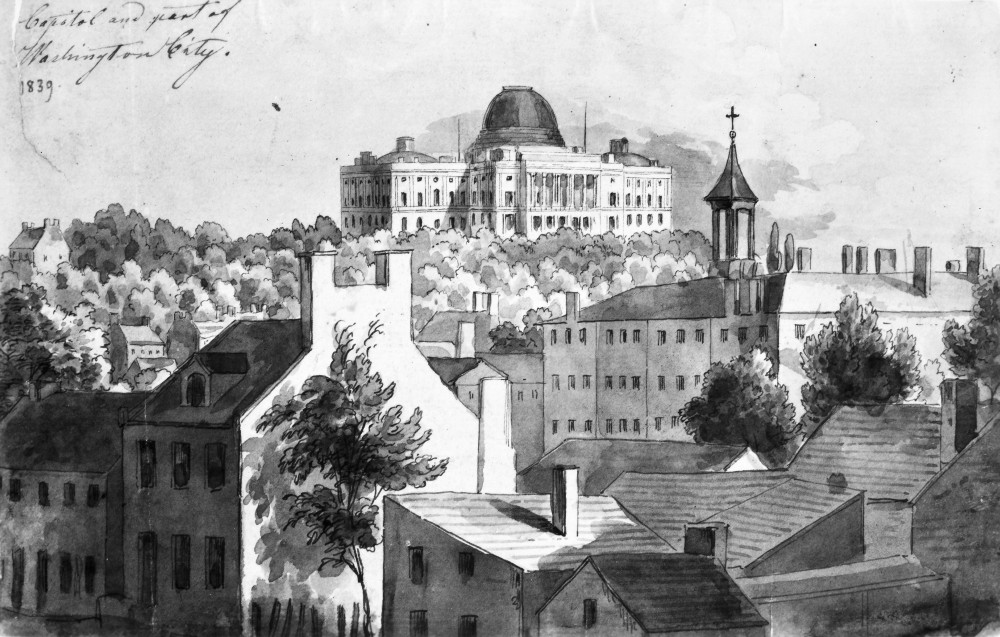

It began on a cold autumn night in October 1839, when Sheriff Thomas Callaway was summoned to the Ashford Plantation, seven miles east of Washington, Georgia. The entry in his official log, later found in a water-damaged courthouse record, was brief: “Domestic disturbance requiring intervention.” Yet beneath that dry phrasing lay a scandal so horrific that it would be buried from public record for more than a hundred years.

At the center of it all was Mary Ashford, a thirty-seven-year-old widow of wealth and breeding — and Daniel Crowe, a thirty-six-year-old enslaved carpenter. Their names, once whispered only in shame, now resurface through surviving fragments: scorched diaries, sealed court transcripts, and the bones unearthed from the red Georgia soil.

The Widow and the Carpenter

The Ashford estate, one of the oldest in Wilkes County, had passed to Mary after the death of her husband, James Ashford, in 1836. Records show forty-three enslaved individuals lived on the plantation — among them Daniel Crowe and his wife, Sarah.

Daniel was valued for his skill as a craftsman, permitted privileges rare among enslaved men. He and Sarah lived apart from the others, in a modest cabin near a stream. Their arrangement — a small mercy granted by the late master — would later become a focal point of tragedy.

By the fall of 1839, Mary Ashford’s mourning had curdled into eccentricity. Neighbors noted she dismissed most of her domestic staff and began calling Daniel to the main house for “repairs.” From the window of her parlor, Mrs. Nancy Wilkinson, a nearby landowner, once glimpsed a tall male figure crossing the veranda at dusk. “Too tall to be any house servant,” she wrote in a letter, “and certainly not one of her kin.”

When Mary began taking meals with Daniel, whispers turned to scandal.

“She Called Him Mr. Crowe”

The journals of Elizabeth Willoughby, wife of the local physician, survive as some of the only firsthand accounts. Her entries — unearthed from an attic trunk in 1954 — reveal a descent into obsession that still chills the modern reader.

“R returned from the Ashford place greatly troubled. He says the widow now calls the carpenter ‘Mr. Crowe’ and insists he wear her husband’s coats. The man appears frightened, but compliant.”

In October, Daniel’s wife Sarah fell gravely ill with tuberculosis. The doctor advised moving her to dry quarters. Mary refused. Weeks later, Sarah was dead.

Two days after the burial, Mary dismissed her remaining housemaids and ordered Daniel to move into the master bedroom.

From there, the story darkened beyond comprehension.

Possession

By winter, Mary had withdrawn from society entirely. She stopped attending church, bolted the plantation gates, and began introducing Daniel to rare visitors as her “husband.”

Willoughby’s journals tell of the horror spreading quietly through the county:

“She parades him before the servants, forcing them to call him Master Ashford. R saw the iron around his ankles. They say she keeps him chained at night.”

Letters from the period describe a “parody of marriage” unfolding within the plantation house — Mary dressed in widow’s silks, Daniel in her late husband’s waistcoat. She forced him to read aloud from her husband’s Bible and sit at the head of the table. The enslaved community lived in terror.

But Daniel’s suffering was invisible to white society. When rumors finally reached the church, Reverend Hyram Parker’s December sermon condemned “unholy unions” that “mocked both God and nature.” Within a week, twelve of Wilkes County’s most prominent men rode out to the Ashford estate.

The Night of December 23, 1839

No official record survives of what happened that night — only fragments of letters, burned and blackened by time.

Thomas Wilkinson, one of the men present, later wrote to his brother:

“We found conditions worse than imagined. The offending party has been removed. The widow is under restraint.”

In 1965, a sealed box was discovered behind a wall in the old county records office. Inside lay a partial transcript of an unofficial hearing conducted on January 2, 1840. It contained testimony never meant for public eyes.

“Found the negro Daniel chained to the bed, dressed in the clothes of the late Mr. Ashford, the widow beside him, both in states of confusion. The woman resisted violently, calling him her husband. The man appeared near broken, alternately silent and raving.”

Sheriff Callaway’s concluding remark read:

“This matter resolved in the best interest of the county. No further record shall be made.”

Daniel Crowe was never seen again.

Madness and Erasure

Mary Ashford was quietly committed to the Georgia State Lunatic Asylum in Milledgeville. The commitment papers cite “moral insanity and delusions concerning her station.”

Seventeen months later, she died — starved and raving — claiming she could still hear Daniel’s chains at night.

Her property passed to a cousin in Savannah, who sold the remaining enslaved workers and the estate itself. In 1847, the main house burned to the ground. No one rebuilt.

The scandal was wiped from the local histories. For more than a century, the name Daniel Crowe appeared nowhere in official archives.

The Rediscovery

In the 1950s, historian Dr. Eleanor Tanner of the University of Georgia stumbled upon references to the “Ashford disturbance” while studying antebellum court records. Her research led her to the hidden journals of Elizabeth Willoughby and a cache of letters long forgotten.

Tanner’s findings suggested not a love affair, but a grotesque inversion of power — a white widow projecting her loneliness and grief onto an enslaved man, stripping him first of agency, then of humanity.

Before Tanner could publish, her university funding was abruptly withdrawn. Her materials “lost in transit.” The silence resumed.

But the truth refused to stay buried.

The Widow’s Diary

In 1963, graduate student Katherine Mercer cataloging donations at the Georgia Historical Society uncovered a small leather-bound diary among the personal effects of the Ashford family’s descendants. It bore Mary’s handwriting.

The final entry, dated December 22, 1839, reads:

“Daniel spoke my name today without prompting. Tonight we shall consummate what God has ordained. They will call me mad, but I am merely blessed. He is mine now, as James once was. We are husband and wife in all but paper.”

The next morning, the men came.

The diary was swiftly confiscated by the Historical Society’s board — deemed “unfit for public study.” Mercer’s access was revoked. Only her transcribed fragments survive, now preserved in a small library in Athens.

A Voice from the North

In 1967, a teacher from Albany, New York, Eliza Crowe, began tracing her ancestry. Her search led her to Georgia — and to the records of an enslaved couple, Daniel and Sarah, listed on the Ashford estate.

In her research, Eliza uncovered a letter written by Dr. Richard Willoughby in 1840 to his brother in Baltimore:

“The negro man was not complicit. He suffered grievously. We sought to erase the shame, but only compounded it. I pray God forgive what we did at the mill.”

That letter transformed the narrative: Daniel Crowe was not a lover nor a transgressor — he was a victim twice over, first of enslavement and then of the widow’s madness.

Evidence in the Earth

In 1968, highway workers uncovered human remains near the old Ashford mill site — later reinterred without investigation. Then, in 2009, ground-penetrating radar revealed a hidden cellar beneath the original east wing of the house — the very area Daniel had been repairing before the widow’s obsession began.

Inside, archaeologists found iron rings set into the walls and faint scratch marks across the mortar. A single silver button, engraved “J.A.,” lay half-buried in the dust.

The findings confirmed what Mary’s diary and Willoughby’s journals had long implied: Daniel Crowe had been kept prisoner.

The Unforgiven Secret

Two centuries later, the Ashford story stands as one of the most disturbing examples of power, race, and obsession in American history — not because it was unique, but because it was documented and then erased.

The tragedy of Daniel, Sarah, and Mary reveals the rot beneath the genteel façade of the antebellum South — where domination and desire intertwined, and where silence became the final act of violence.

A small plaque in the Wilkes County courthouse, installed in 2002, acknowledges “those whose stories were omitted from the historical record.” It names no one. But those who know the truth understand exactly whom it honors.

As one modern historian wrote:

“The ghosts of Wilkes County do not rattle chains. They whisper through documents — the erased, the misfiled, the struck-through lines that still bleed through the ink.”

And on certain autumn nights, locals say, when the frost first touches the ground, the creek near the old Ashford lands runs unnaturally cold — as if the earth itself still remembers.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load