The Victorian Clowns — When Comedy Turned to Murder (1876) | HO!!

I. The Photograph That Should Not Exist

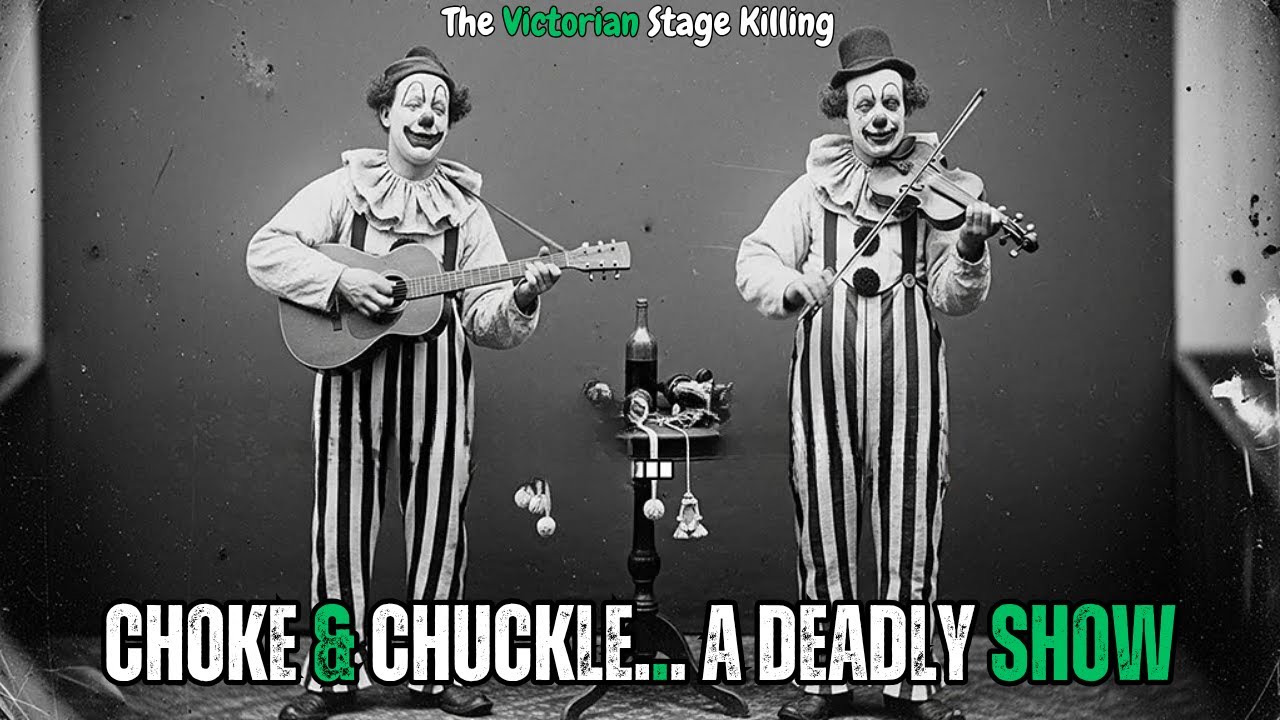

At first glance, the photograph looks harmless. Two Victorian clowns, their faces painted in permanent smiles, stand side by side holding musical instruments — one a violin, the other a guitar. The year is 1876. The caption beneath the faded image reads simply: “Choke & Chuckle, Musical Clowns.”

For decades, this photograph was assumed to be a relic of a lost age of laughter and lighthearted spectacle. But buried beneath the surface is a tragedy so shocking that Victorian society all but erased it from the public record. The duo’s final performance would end not in laughter, but in horror — a grotesque moment witnessed by nearly a hundred people, so traumatic that newspapers censored it and courts sealed the files for fifty years.

This is the story of how comedy, madness, and addiction collided on a small stage in Birmingham — and how a single night destroyed not only two men, but an entire audience’s ability to ever laugh the same way again.

II. A Strange Success: The Rise of Choke and Chuckle

“Choke & Chuckle” began performing in 1872, rising from London’s grimy backstreets to the chaotic world of working-class music halls and freak shows. They called themselves “grotesque musical clowns” — part musicians, part acrobats, part embodiments of Victorian chaos.

Choke, the violinist, was competent if erratic; Chuckle accompanied him on guitar, punctuating each number with wild pantomime and slapstick violence that made audiences roar. Their name came from a peculiar phenomenon that began at their earliest shows: as they performed, spectators eating snacks would start coughing and choking uncontrollably, even as they laughed. The coincidence became their trademark — “The clowns that make you gasp and laugh!” read one Birmingham playbill.

They thrived for three years, but success masked a steady descent into madness.

III. The Descent: Alcohol and Delusion

Choke’s decline was visible to anyone who worked with him. He drank constantly — gin, brandy, anything that dulled the shaking in his hands. He hid bottles in dressing rooms, beneath stage props, even in the soil behind theaters. His violin playing became slurred, erratic, and yet somehow he always managed to stagger onstage, bow in hand, and perform by sheer mechanical memory.

Chuckle’s problems were stranger. What modern psychiatry might diagnose as severe bipolar disorder with psychotic features was, in 19th-century England, simply “eccentricity.” He spoke to invisible people, laughed at jokes no one else had told, and spent hours motionless in a catatonic trance.

The most disturbing stories, however, came from the towns where they performed. Witnesses began reporting a silent clown seen wandering the streets at night after their shows — a white-painted face in the darkness, following women and children through fog-choked alleys, never speaking, never touching, only walking behind them until they reached their doors.

Police dismissed the reports as hysteria. But the sightings spread. By 1875, “the Silent Clown” had become an urban legend whispered from Manchester to Leeds — and the description always matched Chuckle’s costume exactly.

IV. The Night of August 23, 1876

Their final show took place in a third-rate Birmingham music hall, a cramped venue that smelled of sweat, tobacco, and gin. Around eighty people packed the rows — factory workers, families, and children expecting an hour of harmless laughter.

But from the opening act, something was wrong.

Choke staggered onstage visibly drunk, a bottle of gin in one hand and his violin in the other. His bow scratched out sour, dissonant notes. Chuckle, manic and unhinged, leapt and spun with frantic energy, laughing wildly at nothing.

At first, the audience chuckled nervously. The line between comedy and breakdown was thin in Victorian entertainment, and people assumed it was all part of the act. But as Choke’s coordination collapsed, his words turned to curses, and his music to noise, that nervous laughter curdled into silence.

Half an hour in, the routine reached its “interactive” portion — a moment when children were usually invited to join the stage for harmless tricks. Chuckle reached into the crowd and took the hand of an eight-year-old boy sitting beside his mother. The mother hesitated, but smiled weakly and let him go.

The boy climbed onto the stage, beaming.

That’s when everything unraveled.

V. The Moment the Laughter Died

As the boy moved toward center stage, his elbow brushed against the side table — the table where Choke’s gin bottle sat.

It toppled, shattered on the floorboards, and spilled its contents.

The air changed instantly. Choke froze. His gaze locked on the puddle of gin spreading across the wood. The entire room went silent.

He dropped his violin.

In three steps, he crossed the stage and struck the boy. Once. Twice. Again. Full, violent blows — not pantomime slaps, but real punches that broke bone and drew blood.

The audience screamed, but shock held them frozen. It was only when the child collapsed that men began climbing onto the stage. By then, Choke had become a frenzy of rage — roaring, swearing, blood on his white gloves.

And through it all, Chuckle laughed.

He clapped his hands, jumped in circles, and played to the audience as if this horror were part of the show. His mind had fully detached from reality. When rescuers dragged Choke away, Chuckle picked up the broken violin and began playing screeching, discordant notes — his shoes leaving red footprints across the boards.

By the time the mother reached her son, the child was gone. He had died within minutes from massive cranial trauma.

VI. The Aftermath

Police arrived fifteen minutes later. Both clowns were arrested. The mother was sedated and taken to a nearby hospital after collapsing beside her son’s body.

Witnesses later described the audience’s reaction with words that would appear in early psychological journals decades later: collective trauma. Dozens remained seated, staring at the bloodstained stage long after the arrests. Some cried silently; others trembled.

The following morning, local papers printed only vague notices: “Disturbance at Music Hall. Two performers arrested following unfortunate incident.”

Privately, city officials ordered editors not to report the full details.

VII. The Trial and Execution

Six weeks later, the trial of Henry “Choke” Whitmore and Edgar “Chuckle” Reeves opened in Birmingham. The courtroom was packed. Eighty eyewitnesses testified.

Choke’s defense claimed temporary insanity brought on by alcohol. Chuckle’s lawyers argued for mental incompetence. Neither plea mattered. The evidence was overwhelming, and the crime unforgivable.

Both men were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to hang.

On October 12, 1876, they were executed inside Birmingham Prison — public hangings having been abolished eight years earlier.

Witnesses said Choke met his death without expression, his face blank. Chuckle smiled faintly under the black hood, whispering to the executioner:

“Is it time for the next show?”

VIII. The Ghosts of Birmingham

The music hall where the killing occurred was closed immediately. Its owner, unable to sell it, eventually had it demolished in 1880, the timbers burned to “purify” the site.

Locals swore they could still hear laughter in the empty lot — high, brittle giggles echoing through the fog. Others claimed they heard violin notes drifting from nowhere, mingled with the sound of a child crying.

The mother, whose name was withheld from records, was committed to an asylum months later for “melancholia and delusions.” She died there in 1879.

For decades, the tragedy lived on only as whispers. Newspapers were ordered to destroy their notes; families were told to “forget.” Yet memory, like smoke, seeps through any wall. Parents told their children in hushed voices about the night the clowns went mad.

By the 1920s, when court records were finally unsealed, the legend had mutated into folklore: a tale of demonic jesters who killed for sport, of cursed laughter that could choke the soul.

The truth was simpler, and far more terrifying.

IX. What We Choose to Forget

The tragedy of Choke and Chuckle wasn’t just the act of two broken men — it was the failure of a society that looked away.

Victorian England profited from pain. Freak shows and “lunatic clowns” drew crowds because audiences found comfort in watching madness at a safe distance. Alcoholism was laughed off as “manly vice.” Mental illness was ignored until it spilled blood.

The signs were there all along — the drunkenness, the hallucinations, the stalking in the streets — but no one intervened because the tickets kept selling.

What happened on that stage wasn’t spontaneous madness. It was the final act of a performance the entire society had written.

X. The Photograph

Today, the only surviving image of Choke and Chuckle rests in a museum archive — a sepia photograph labeled “Unknown Performers, 1876.”

Their faces are fixed in permanent smiles. Their instruments gleam faintly under the light. And if you look closely, you can see a faint dark mark at the edge of the frame — a child’s hand, blurred by movement, forever frozen beside them.

The hand of the boy who never went home.

If this story unsettled you, it should.

The story of the Victorian clowns reminds us that the line between comedy and cruelty is thinner than we like to believe — and that laughter, when built on the suffering of the broken, always ends in silence.

Because sometimes, the show must not go on.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load