The “ᴜɢʟʏ” Slave Who Became the Most Desired Man in the South (Louisiana, 1845) | HO!!

The story begins, as many Southern tragedies do, with a ledger.

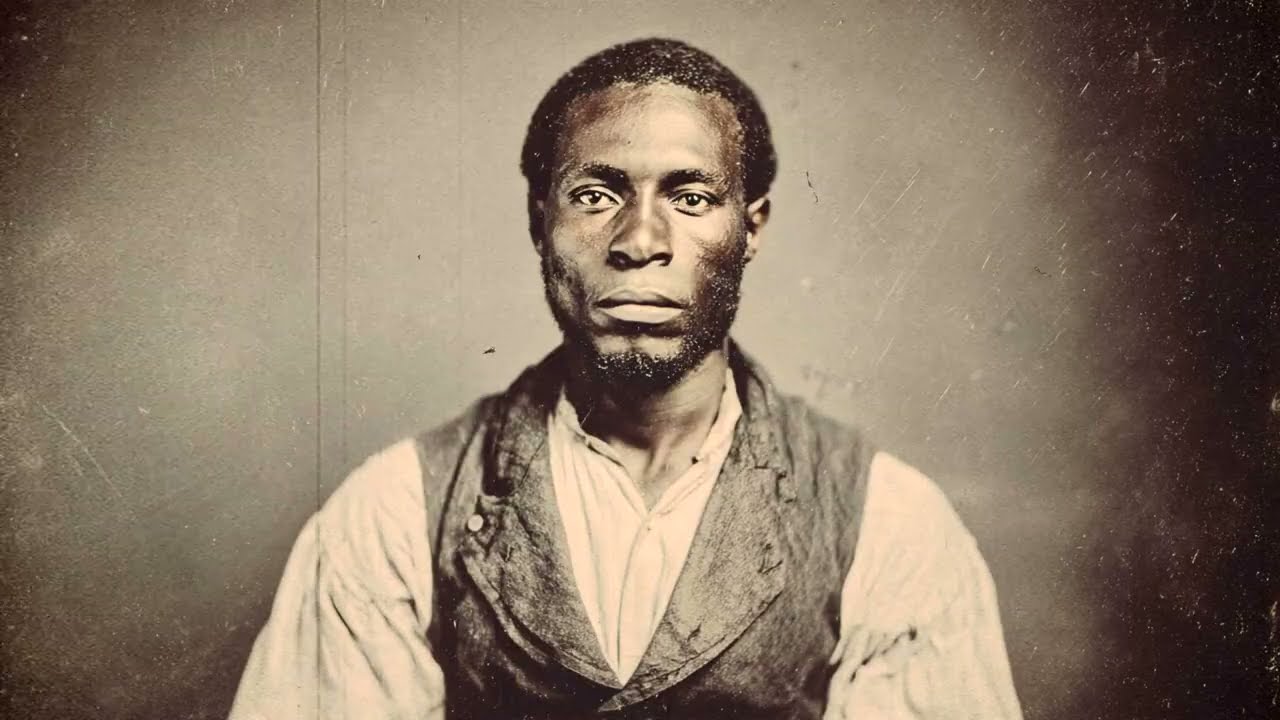

In April 1845, in the parish of St. Landry, Louisiana, an unremarkable name appeared among the auction records: Ezekiel. Purchased for a fraction of the market price, described as “of no notable appearance,” he was one of dozens sold that day to supply the ever-hungry plantations of the American South.

No one could have predicted that this man — purchased cheaply, almost as an afterthought — would become the center of one of the most psychologically disturbing episodes in antebellum history.

The House That Grew Too Quiet

The Willoughby Plantation, twelve miles east of Opelousas, was one of the grandest estates in the parish. Its owner, Augustus Willoughby, was known for his orderliness; his fields were productive, his records exact, his reputation untarnished.

His wife, Margaret, was rarely seen outside the estate. Their daughters had married into families in New Orleans and rarely returned. The rhythm of the plantation life — harvests, accounts, and sermons — seemed eternal.

But within months of Ezekiel’s arrival, that rhythm began to falter.

The overseer, Jeremiah Palter, whose detailed journals would later become invaluable to historians, first noted something odd:

“The new man, Ezekiel, demonstrates uncommon aptitude for repairs. Reassigned to maintenance.”

Weeks later, another entry:

“Reassigned to household duties.”

That, Palter noted, was unheard of for a man purchased for field labor. Yet no one objected.

Then, a letter surfaced decades later, written by Margaret Willoughby to her sister in Charleston:

“There is something about the new servant. His presence silences a room. I cannot explain it. Augustus insists he is useful, but I find myself… unsettled.”

The Women Who Couldn’t Stay Away

By winter, rumors began to circulate.

Ezekiel’s appraised value had mysteriously tripled. Neighboring estates began sending written requests to “borrow” him — particularly the Clareborn Plantation, whose mistress, Ellen Clareborn, personally signed for his service four times in two months.

By early 1846, Palter’s visitor log showed a flood of female visitors — more than twenty in February alone — arriving from as far as Baton Rouge and New Orleans. They came under various pretenses: delivering messages, visiting Margaret, purchasing cloth. Yet each stayed for hours.

Something was happening inside the Willoughby household that no one dared name.

The Reverend’s Warning

On March 12, 1846, Reverend Thomas Whitfield wrote a letter to Augustus Willoughby:

“Grave rumors abound concerning your household and a certain individual therein. For the preservation of moral order, I urge his removal to a distant property.”

Willoughby ignored him.

Weeks later, Palter’s tone darkened:

“The mistress has taken to her bed with nerves. The master denies all impropriety. The wives of our neighbors appear at odd hours. It is as if the parish has gone mad.”

What was it about Ezekiel — this “unremarkable” man — that drew women of the South’s ruling class to him like moths to flame?

The Panic in St. Landry

In May 1846, plantation owners convened an emergency meeting. The minutes, discovered a century later, spoke in veiled language but revealed a collective fear:

“The presence of a certain man has caused domestic unrest and moral danger of unprecedented scale.”

A resolution was passed: Willoughby must sell him, or face social and financial ruin.

Willoughby’s response, preserved in draft form, was blistering:

“What you fear is not this man, but the reflection of yourselves you see in him. He has done nothing but exist within the system you built. If his mere existence threatens it, then it is the system — not the man — that is diseased.”

It was an act of defiance that would destroy him.

The Night of the Gathering

The crisis reached its breaking point on September 2, 1846.

According to a sheriff’s report, more than thirty women from the region — wives and daughters of Louisiana’s most powerful men — were seen walking the roads toward the Willoughby estate just after midnight.

Their behavior, the report said, was “translike.”

They gathered not at the main house, but near the quarters where Ezekiel slept. Armed overseers from neighboring plantations arrived to intercept them. A confrontation ensued. Shots were fired.

By dawn, Ezekiel was gone.

No body was ever found. No official inquiry followed. The women were quietly returned to their homes, many of them later sent away “for their health.”

Within weeks, the Willoughbys fled Louisiana for Europe. The plantation changed hands, its records conveniently destroyed in a courthouse fire the following year.

The Letters That Should Not Exist

Nearly a century later, in 1962, carpenters renovating the abandoned Clareborn estate discovered a false compartment in an antique writing desk. Inside were twelve letters — all addressed to Ezekiel.

They were written in an elegant feminine hand.

“In your presence,” Ellen Clareborn wrote, “the lie we have all lived becomes impossible. You make us see that our lives rest upon cruelty disguised as grace. What frightens me most is that you do not curse us — you only see us.”

“They call you dangerous,” another letter read, “but it is not you they fear. It is the selves you awaken within them.”

None of the letters appear to have been sent. Historians believe they were hidden out of terror — or shame.

The Man Who Wouldn’t Break

To those who encountered him, Ezekiel seemed neither seductive nor charismatic in any ordinary sense. His power was subtler — and infinitely more dangerous.

As one diary entry recorded:

“He is not handsome. But there is something in his eyes — a calm that undoes you. As if he looks not at you, but through you.”

For the women of Louisiana’s planter class — confined in gilded cages of obedience and hypocrisy — such a gaze was intolerable. It stripped away the social theater, revealing what lay beneath: complicity, emptiness, fear.

The system depended on blindness. Ezekiel made them see.

After the Vanishing

The aftermath was a collapse of order.

Within months, eleven plantation families sold their holdings or relocated. Parish records cite “health concerns,” but correspondence between owners tells another story:

“Some places become uninhabitable,” one letter reads, “not through decay, but because one can no longer bear to look in the mirror.”

Women formerly of high standing were quietly committed to asylums or sent north to live with relatives. Ministers spoke of a “crisis of faith” spreading among their congregations.

One clergyman wrote, “They confess sins not of action but of thought — an awareness that their entire world is built on falsehood. They ask questions no sermon can answer.”

Echoes in the North

Then came the rumors.

Reports surfaced in Mississippi (1847) and Ohio (1848) of an articulate freedman known only as “Z.” He spoke rarely, but when he did, listeners claimed his words “stripped away lies.”

Underground Railroad records from Philadelphia (1847) describe assisting “a man of deep composure whose gaze unsettled all who met him.”

And in Chicago, a journal discovered in 1959 recorded a chilling recollection by a woman who had fled the South:

“They called him ugly because they feared the truth in his face. We desired not his body, but the freedom he carried. To see him was to know the prison we had built around ourselves.”

The Mirror That Could Not Be Shattered

In 1887, the Louisiana Historical Society received an unsigned letter from Chicago, postmarked under the name Isaiah Freeman. Handwriting experts later matched it to samples from Ezekiel’s overseer logs.

“They feared not me, but the truth of what I represented,” it read.

“I was a mirror in which they saw themselves clearly. They called me ugly because the reflection was unbearable.”

“The ghost that haunts the South is not me, but the instant when self-deception fails.”

If Ezekiel truly became Isaiah Freeman, he lived to teach, write, and die in 1892 — free in body and mind.

The Horror of Seeing Oneself

Modern historians call the Willoughby incident “a psychological insurrection.”

No rebellion, no bloodshed — only the collapse of illusion.

Dr. Elaine Richardson’s 1983 study The Psychological Architecture of Slavery described it as:

“The Willoughby phenomenon — the moment when a system of domination fractures under the unbearable weight of its own lies.”

To the women of St. Landry Parish, Ezekiel’s presence was an apocalypse of perception. He forced them to see their privilege as imprisonment, their civility as cruelty, their refinement as rot.

He did not free them. He made them realize they had never been free at all.

The Land That Still Feels Different

Today, nothing remains of the Willoughby estate. The land is farmland now, crossed by a narrow creek.

But locals still speak of “the bright spot” — a place where, for reasons they can’t explain, “the air feels lighter, as if something’s been revealed.”

Perhaps it’s superstition.

Or perhaps it’s the echo of a man who, by simply existing without shame, undid an empire of lies.

Ezekiel — the “ugly” slave who became the most desired man in the South — never wielded a weapon, never raised his voice, never demanded vengeance.

He only looked.

And in that gaze, the South saw itself — stripped bare of myth, trembling before the mirror of truth.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load