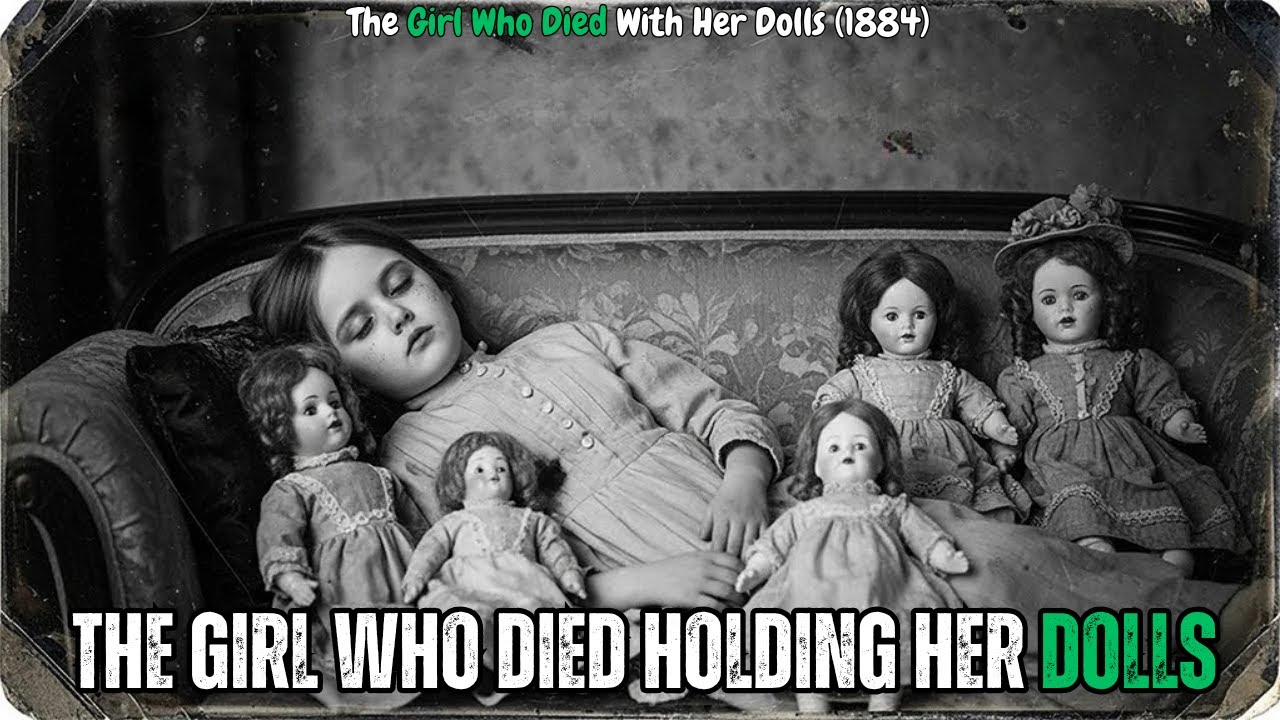

The Tragic D3ath of Rose Cavanaugh — A Post-Mortem With Her Dolls (1884) | HO!!!!

A Photograph That Shouldn’t Exist

In the winter of 1884, in a small manufacturing town somewhere in New England, a local photographer named Joseph Mand set up his tripod in the parlor of a modest red-brick home. Before him lay a girl of nine, dressed in white lace, her hands folded over five porcelain dolls. Her name was Rose Kavanagh—and she was dead.

To most, the resulting image would appear to be one of the countless post-mortem photographs taken during the Victorian era, a time when death was not hidden but ritualized. Families treated these portraits as sacred relics—tokens of remembrance in a world where epidemics and accidents routinely stole children long before their time.

But this photograph is different. Behind Rose’s serene expression and the stillness of those glass-eyed dolls lies a tragedy so haunting that even now, more than a century later, archivists and collectors whisper about its curse.

The Dollmaker’s Daughter

The story begins with the Kavanagh family, owners of The Caverner Doll Shop, a respected establishment on the town’s main street. Frederick and Sarah Kavanagh were artisans of reputation: he imported fine porcelain heads and limbs from Europe; she hand-stitched elaborate dresses that turned each doll into a miniature Victorian lady.

And then there was Rose, their only child—bright, imaginative, and adored by the community. To local children, she was the “little lady of the shop,” the one who could look into a child’s eyes and somehow know which doll would suit her best.

But Rose’s fascination went beyond business. She spoke to the dolls, gave them names, and insisted each had a soul. By the age of six, she was sewing miniature clothes. By seven, she was painting faces. At eight, she was crafting full dolls of her own—each one unique, as if born from her small but gifted hands.

A Child’s Secret of Kindness

Among the shop’s daily visitors were the orphan girls from the municipal asylum at the edge of town—a bleak, overcrowded institution that few wanted to speak of. They would press their faces to the glass, mesmerized by the dolls they could never afford.

Rose couldn’t stand it. Quietly, she began to make her own dolls from spare porcelain pieces and scraps of cloth, hiding them in a basket under the counter. When her parents were distracted, she slipped out the back door and placed a doll into the hands of a waiting child. “Don’t tell,” she whispered.

For months, her secret acts of kindness continued. But in a small town, secrets are fragile.

One day, a customer—Mrs. Morland, the neighborhood’s most prolific gossip—remarked how peculiar it was to see orphan girls with dolls that looked just like the ones in the Kavanagh shop. That night, Frederick took stock. Twenty dolls were missing.

The Father’s Fury

The confrontation came the next afternoon. The October sky was the color of iron when Frederick called his daughter into the small back office. He accused her of theft—of disrespecting the family’s sacrifice.

Rose sobbed, pleading that she only wanted to make the lonely children happy. But her father’s pride, already strained by declining profits, blinded him. He forbade her from entering the shop, from touching the dolls, even from her evening walks.

Sarah tried to soften him, but he was immovable. “She must learn what her actions cost,” he said.

That night, Rose sat by her window, clutching four of her favorite dolls: Mary in her sky-blue dress, Matilda with red curls and green lace, and two unnamed creations of her own design. Outside, fog rolled down from the hills, muffling the sounds of the town. Somewhere between tears and exhaustion, she whispered to her dolls, telling them she wished she could run away—somewhere they would all be free.

The Fog by the Lake

When morning came, Rose’s bed was empty. The window stood open. The dolls were gone.

Panic gripped the house. Frederick sprinted through the streets shouting her name. Sarah ran to the orphanage, desperate for any sign. Neighbors joined the search, combing through barns, alleys, and the woods beyond the mill road.

It was late afternoon when a farmhand noticed footprints by the lake—small ones, leading into the shallows. Floating near the reeds was a scrap of blue fabric.

What followed became legend in the town’s oral history: the men wading into the icy water, Sarah screaming on the shore, and the moment they carried out the small, lifeless body of Rose Kavanagh, still clutching her four dolls to her chest. Witnesses said her arms were locked around them, as if they were the only companions she trusted to follow her into death.

Dr. Henry Fairchild recorded the cause as drowning—“most likely accidental.” But everyone in town knew there was more to it than that.

A Death That Would Not Let Go

Guilt consumed Frederick. He stopped eating, stopped speaking to customers. He couldn’t look at a doll without seeing his daughter’s face. Sarah drifted through the house like a ghost, lingering in Rose’s room for hours, waiting for a voice that would never return.

Then came the idea of the post-mortem photograph.

At the time, such portraits were common—acts of devotion rather than morbid curiosities. Families dressed the deceased in their finest clothes, posed them as if sleeping, and captured a final image to preserve the illusion of peace.

Sarah washed and combed Rose’s hair. Frederick polished the dolls she had taken to the lake. They arranged her on the Victorian sofa where she used to play, surrounded by those same dolls. A fifth was added—one Sarah said had been Rose’s favorite.

When photographer Joseph Mand entered the parlor, even he—accustomed to death—felt uneasy. The fog outside dimmed the light; the house was unnaturally still. As he peered through his lens, he later swore he saw one of the dolls move its head ever so slightly.

He blinked. The figure was motionless again. Perhaps, he thought, it was only the trick of a trembling hand. But until the end of his life, he claimed that something alive was present in that room.

The Photograph on the Wall

The print was ready days later. Frederick had it framed in dark walnut and hung behind the shop counter—a shrine to the daughter who had loved the dolls more than profit.

But customers recoiled. Some said the photograph gave them chills. Others claimed the girl’s closed eyes seemed to follow them. Children who once ran through the aisles now grew silent in her presence.

Soon business dwindled. At night, Sarah dreamed of her daughter calling from beneath the lake. Frederick heard small footsteps upstairs after closing, though the house was empty. Once, he found one of Rose’s old dolls sitting on the parlor sofa—the very spot where the photograph had been taken.

Haunted and desperate, Sarah suggested transforming Rose’s secret generosity into something good. The Kavanaghs began donating dolls each month to the orphanage, a gesture that softened public sentiment and slowly revived the shop. But Frederick’s guilt never lifted.

Often he stood before the photograph after closing, whispering apologies to his daughter. “Forgive me,” he’d say. “Forgive me.” Sometimes he swore he felt a presence—soft, forgiving—beside him.

A Family Caught Between Worlds

Years passed. The Kavanaghs had another child—a boy named John. He grew up in the shadow of the photograph, hearing stories about the sister he never met.

To him, the image was not frightening. It was family. He claimed he sometimes felt her near, as if the air itself shifted gently when he passed her portrait.

The doll shop endured for three more decades, becoming both a business and a memorial. When Frederick died in 1912, he was buried with a small copy of the photograph in his pocket. Sarah followed two years later.

Even after the shop closed in the 1920s, tenants who rented the building reported eerie happenings: the faint patter of small footsteps upstairs, the tinkle of a music box playing without wind, and on rare nights, the silhouette of a little girl in a Victorian dress standing at the window, gazing down at the empty street.

The Photograph’s Afterlife

When John Kavanagh died in the 1950s, the photograph passed to a distant relative, who eventually sold it at auction. Since then, it has traveled through collectors’ hands across the decades, each leaving behind a new story.

One man in the 1960s claimed he dreamed of drowning while holding dolls. A woman in the 1970s heard a lullaby playing in her house after acquiring the photo—though she owned no music box. In the 1980s, a historian studying Victorian mourning customs reported “a presence” watching him from behind the glass.

Today, the photograph resides in a public archive, mislabeled simply as “Unidentified Girl with Dolls, ca. 1884.” The name Rose Kavanagh is nowhere to be found. Yet those who study it closely can sense that her story lingers—just beneath the surface of the image.

The Mystery That Never Fades

Modern historians confirm that a nine-year-old Rose Kavanagh drowned in October 1884, and that her parents indeed owned a doll shop on Main Street. A surviving letter from Sarah, written three years after the tragedy, describes her grief—and her conviction that their monthly donations were “guided by Rose’s hand.”

Whether Rose’s death was an accident, a child’s impulsive act, or something more unearthly, no one will ever know. What endures is the image: the pale girl among her porcelain companions, forever poised between worlds.

Some believe her spirit lives within the dolls; others see in the photograph not horror, but an enduring testament to love, guilt, and redemption.

Whatever truth lies hidden in the silver emulsion, the photograph continues to command a strange power. Look long enough, and you might feel it too—that faint, electric sensation that you’re being watched.

Perhaps by a child who once gave her dolls to those who had none.

Perhaps by the memory of every word left unspoken.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load