The Slave Who ʙᴜʀɴᴇᴅ 8 Masters Alive Inside a Mansion – South Carolina’s Macabre Night (1823) | HO!!

Charleston District, South Carolina — January 18, 1823

A brief paragraph appeared that day in the Charleston Mercury under “Local Items”:

“Fire claims Willowbrook estate. Eight souls perish.”

No fanfare. No investigation published beyond that. No mention of names. The case was filed away, the official explanation: a house slave named Solomon set the blaze — executed in short order. But beneath the veneer of closure lies something far darker, and far more elaborate.

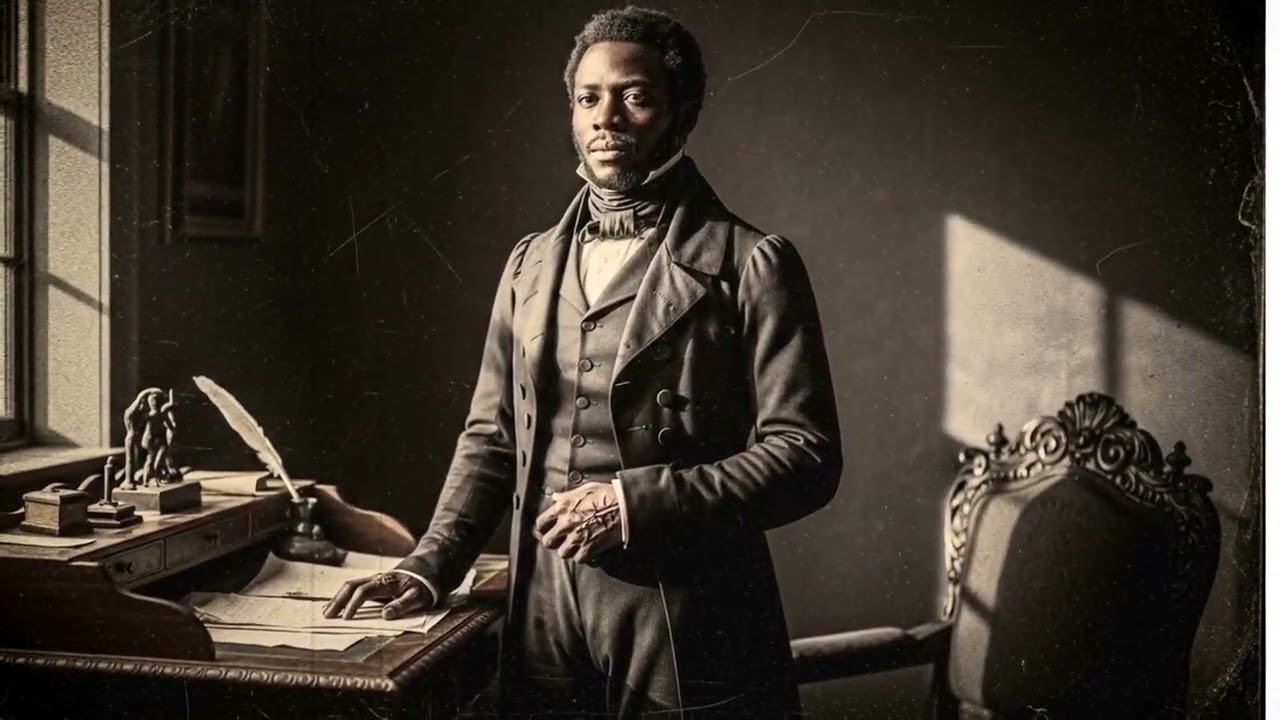

The Man, the Mansion and the Meal

The estate was known as the Willowbrook Plantation, owned by Judge Thaddius Blackwood, a pillar of Charleston society, whose Sea Island cotton and legal pronouncements earned him respect from the busy port to far-northern courts. His family name held sway across the Carolinas.

And yet, what the polite society of Charleston did not discuss: the speed with which house-servants came and went in his household. Why few lasted more than two years. Why his personal impress seemed more exacting than most.

On the night of January 15, 1823, Blackwood invited eight male guests — fellow planters, bankers and political associates — to dinner at Willowbrook. The invitations were unremarkable; the company, discreet. What made the evening fatal: none of the men left.

By 2:00 a.m. the next morning, the estate was ablaze. The main house doors were barred from the outside, every first-floor window nailed shut. The men perished by smoke inhalation in Judge Blackwood’s study, according to the coroner’s minimal report.

Meanwhile, a house-slave named Solomon (approximate age 30) was arrested as he attempted to board a north-bound vessel in Charleston Harbor with only a sealed letter and a ring belonging to Blackwood in his possession. He stood no trial. Within 24 hours he was hanged. The letter later disappeared from records, the ring melted. Case closed.

The Unasked Questions

That official narrative invites more questions than answers. Why were all eight men found together in a locked study, with the doors and windows sealed? How could the fire initiate simultaneously in four discrete locations? Most unnervingly: why were fine boot-prints leading away from the mansion, matching expensive leather footwear owned by Judge Blackwood himself?

For decades, the Willowbrook fire faded from memory. The land around the mansion was left untouched; local children deemed the site taboo. The Blackwood name receded. In 1861 a Confederate survey team commented on “substructure extending beneath main house— not in original plans” — yet no follow-up investigation followed. The estate changed hands repeatedly between 1865-1900; no development succeeded.

Hidden Chambers & Smuggled Cargo

In 1932, historian Martin Abernathy of Clemson University uncovered Judge Blackwood’s business dealings: eight men at the fatal dinner were investors in a shipping company that lost three vessels in 1822, insurance claims paid despite suspicions of deliberate scuttling. Abernathy theorised Willowbrook’s sub-cellar might have held illicit cargo: human lives rather than goods. He requested excavation, was denied, and abandoned research after his office was broken into and his notes stolen.

In 1958, historian Rebecca Sullivan found a WPA-era slave narrative from coastal SC: an enslaved grandmother claimed Solomon was literate—highly unusual—and had been purchased by Blackwood from Virginia at ten times the going rate, “subject meets all specifications.” Sullivan uncovered a pre-fire survey map of Willowbrook showing a substantial structure beneath the main house, accessed via the wine cellar — a feature omitted in later renderings.

In 1968, workers uncovered a mass grave near the site: circa 40 African-descent skeletons, carbon dated 1820-23, many with grooves on wrists/ankles consistent with shackles, signs of starvation/dehydration. The report was classified and quietly buried. Could Willowbrook have been a holding-pen for smuggled slaves?

A Slave, a Judge, and the False Verdict

What role did Solomon play? Officially, a lone culprit bent on vengeance. But the evidence hints at something else: perhaps Solomon was purchased by Judge Blackwood for his literacy, not for field-work — to translate or interpret something found in the underground chambers.

The boot-prints, the sealed rooms, the simultaneous arson locations, the disappearance of Blackwood’s body (never recovered) — all point to a conspiracy rather than singular rebellion. Some historians suggest Blackwood and Solomon staged the fire, faked deaths and fled, perhaps to New Orleans or Boston under assumed identities.

A tin box discovered in 1965 allegedly contained a journal dated January 1-15, 1823, signed ‘S.’ It spoke of “chambers of death beneath the house,” and a plan to bring justice where the law would not. The box disappeared shortly after. Joseph Miller, the worker who found it, was soon black-listed.

.jpg)

Legacy of Silence

The site today remains undeveloped in Charleston County. Local resident reports: compasses misbehave near the foundation; electronics fail; children dare not approach the overgrown ruin. In 2002, a portion of ground collapsed revealing a stone archway ~15 ft deep, with unfamiliar symbols carved into stone blocks, which county officials hurriedly sealed with concrete.

What do we make of Willowbrook? A slave rebellion? A smuggling operation gone awry? A cover-story for a deeper secret? The eight masters gathered that night were not simply guests; their business interests connected to Blackwood’s maritime ventures. The house slave Solomon may have been a translator in the shadows — or the scapegoat. The judge may have perished — or escaped, his façade extinguished in fire.

A Final Reflection

The fire of January 1823 at Willowbrook is more than a historical oddity. It is a testament to how power shapes narrative, how the truth is sometimes buried—lit by flame, sealed by authorities, and forgotten by design. History’s footnotes often hide the most haunting stories.

What we know: eight prominent men died; a house-slave was executed; the main document vanished; the secret architecture was hidden; and the land remains unsettled. What we don’t know: what was unleashed beneath that mansion, worth burning eight men alive and erasing a judge’s legacy?

Perhaps the greatest legacy of Willowbrook is this: some fires are started not to destroy—but to contain. What lies beneath may never be brought into the light.

And so, if you ever drive past Charleston’s forgotten foundations, listen for the silence. The land keeps its secrets well.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load