The Savannah Noblewoman Who Fell for Her Slave… Until Her Family Ordered His D3ath | HO

In the archives of Chatham County, Georgia, lies a sealed collection of papers that few historians have been permitted to read. Court-sealed in 1964, these documents were said to contain the private correspondence, diaries, and legal records of one of Savannah’s oldest and most powerful families — the Whitmores.

For over a century, their name appeared only in respectable histories: judges, landowners, pillars of Southern virtue. But in the spring of 1959, an Emory University researcher stumbled across something buried beneath the floorboards of the Whitmore estate — three leather-bound journals written by Eleanora “Elellanena” Whitmore, the judge’s youngest daughter.

What those journals revealed — and what the university later buried — told a story of love, betrayal, and murder that Savannah society would never forgive.

The House by the River

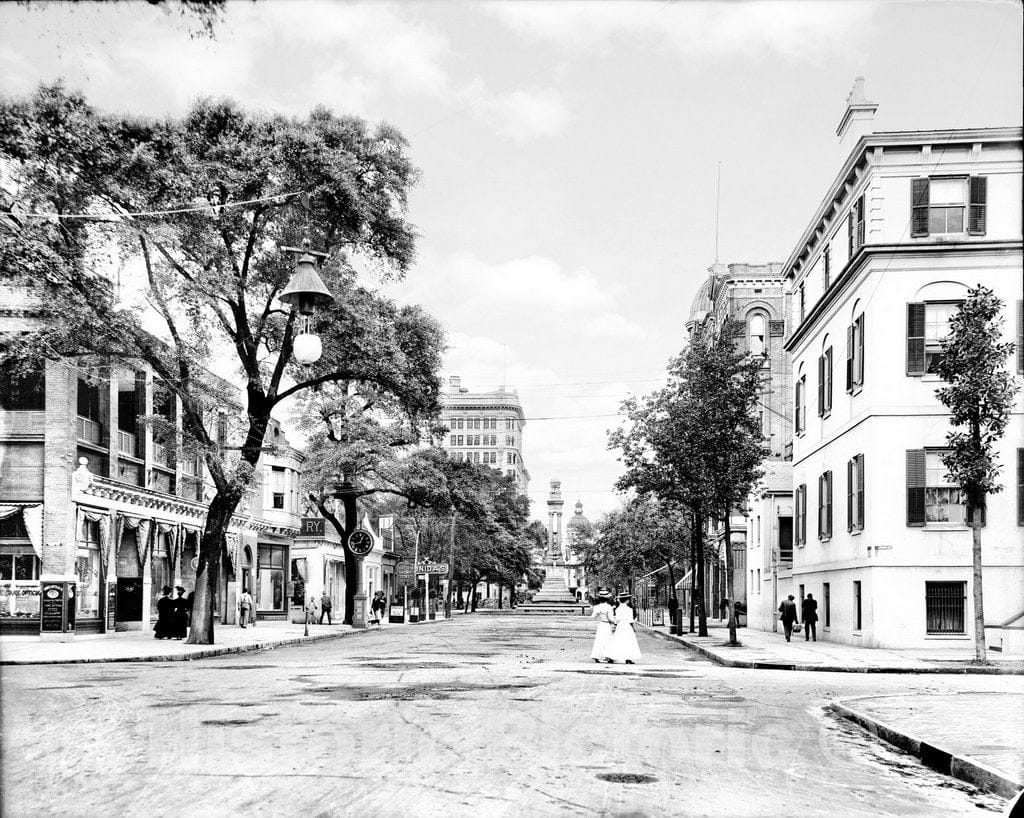

The Whitmore plantation stood three miles outside the city, its white columns gleaming against the Spanish moss that hung from ancient oaks. Built in 1798, it overlooked the Savannah River — the same river that carried cotton, tobacco, and, in darker shipments, human beings.

By 1840, Judge Nathaniel Whitmore ruled his estate and much of the county. He had two daughters: Catherine, the obedient wife of a neighboring planter, and Elellanena, twenty-six, unmarried, educated, and, by the whispered accounts of Savannah society, “unsettled.”

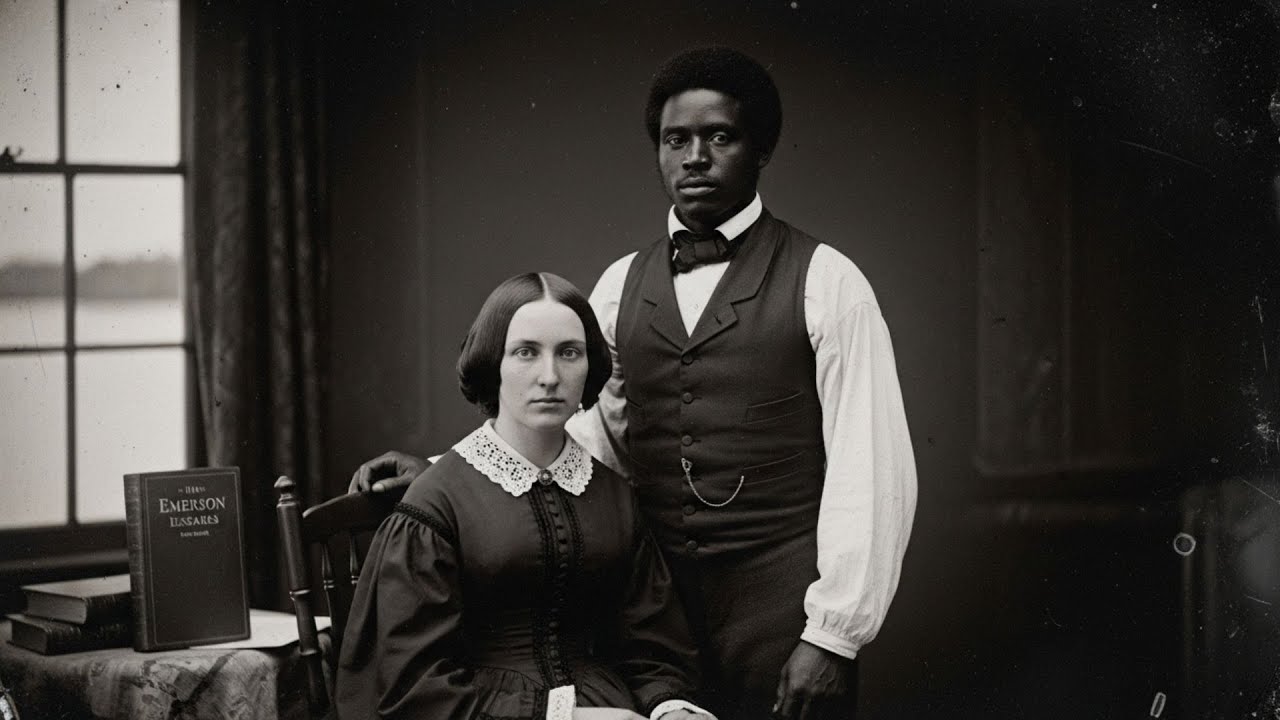

Her first surviving diary entry concerning the man who would change her life forever is dated April 17, 1840:

“Father has purchased ten new field hands. One man looked up as they passed the house. His eyes held no fear, only a strange dignity. His name, they say, is Thomas.”

His full name was Thomas Avery, a thirty-year-old carpenter purchased for $800 — unusually high for an enslaved man. Avery claimed to have been born free in Pennsylvania before being kidnapped and sold south. The judge dismissed the claim as “Northern nonsense.”

Within weeks, Thomas was reassigned from the fields to carpentry work around the main house. And before long, he was repairing the staircase outside Elellanena’s room.

The Book of Emerson

Her diary grows more detailed, more intimate.

“Today I brought books to the workshop. He can read — though he pretends otherwise before the others. I left him a copy of Emerson’s essays. He asked if I wished something in return. I told him only conversation.”

Soon, the entries reveal long talks about freedom, philosophy, and the nature of conscience — dangerous topics in a household where even words could be punished.

By autumn, the plantation was filled with rumors. Two enslaved workers claimed to have seen a white woman walking alone near the quarters at night. A barn caught fire. River patrols increased.

Judge Whitmore left for Charleston on business in September. In his absence, Elellanena’s diary became a confession:

“He says there are people who would help us reach the North. I tell him he speaks madness, yet each day I dream of it. I am to be sold in marriage, just as he is bought and sold.”

The Discovery

On November 10, 1840, the overseer, Samuel Reynolds, wrote a letter to the judge:

“Sir, I must bring to your attention the behavior of Miss Eleanor. She has been seen passing papers to the carpenter Thomas. I await your instructions.”

The judge returned five days later. Plantation punishment records — usually meticulous — show a gap that week.

When Elellanena’s diary resumed on December 1st, her handwriting was shaky:

“I am watched constantly. They say I am ill. The laudanum clouds my thoughts. Father speaks only of my engagement to Mr. Harrison. They will send me away if I do not behave.”

The sale records for that month list Thomas Avery as sold “to a Mr. Smith, New Orleans,” for $550 — a loss that made no business sense. The entry was scribbled in haste.

Catherine Whitmore’s diary for November 25th provides a chilling corroboration:

“Father says Eleanor’s melancholy is the result of fever. She hardly speaks. When I mentioned the servants who’ve gone missing, she turned to me with such hatred I scarcely knew her.”

The River Problem

In December, Eleanora was seen wandering near the docks at midnight, speaking to a boatman. The City Watch detained her. The judge intervened. The matter vanished from public record.

Her next entry:

“I have learned to play their game. I smile. I speak of the wedding. They believe I am cured.”

Then came January 23, 1841 — a date that would haunt Savannah for generations.

That night, gunshots were heard near the river. Two ships departed earlier than scheduled. A payment of $100 appears in Judge Whitmore’s private ledger beside a cryptic note: “River problem resolved — Johnson Brothers.”

The next morning, Eleanora wrote:

“The blood will never wash from this house. They call it justice, but I know it for what it is. They fear I will harm myself. They do not understand that I am already dead.”

Thomas Avery was never seen again.

The Wedding and the Fall

On February 20, 1841, Savannah’s society pages celebrated “the most elegant union of Miss Whitmore and Mr. James Harrison.” The bride was pale but “composed.”

Six months later, the judge sold the plantation and moved the family to Atlanta.

Three years passed. Then, on April 4, 1844, Charleston newspapers announced:

“Tragic accident — Mrs. Eleanora Harrison drowned during last night’s storm. Her husband awoke to find the balcony doors open.”

The city called it a tragedy. Some whispered it was judgment.

“Tell Him the Child Bears His Name”

In 1962, among the papers of a Philadelphia minister, historians discovered a letter dated March 1844, weeks before her death. It bore no signature, but the handwriting matched her diaries:

“Reverend Peterson,

I write regarding a man who may have sought your aid three years past. His name is Thomas Avery, carpenter. If he lives, tell him only this: I kept my promise. The child bears his name as a middle name. She will be sent north to school, away from this place and all it represents.”

Records show that fifteen years later, in 1859, Peterson’s church sponsored the education of a girl named Elizabeth Thomas Harrison — age fourteen, from Charleston.

She would later teach freed slaves in Philadelphia after the Civil War. Her tombstone, dated 1912, bears a single inscription:

“She carried forward what others could not finish.”

The Bones by the River

In 1963, construction near the old Whitmore property unearthed a skeleton at the river’s edge. The bones showed evidence of violent trauma. A gold ring was found nearby — an item enslaved men were rarely permitted to own.

Before further study could be done, the remains were reburied under a new foundation. The medical examiner’s report was sealed by court order within the year.

The Emory researcher who discovered Eleanora’s journals tried to publish her findings. Soon after, she began receiving threats. The university withdrew its support, and she vanished from academic records entirely.

The archives were sealed “to protect the reputations of prominent Georgia families.” They remain sealed to this day, not to be opened until the year 2100.

Echoes in the Water

Even without the documents, the story refuses to die.

Residents near the old Whitmore land claim that on January nights, the Savannah River turns strangely restless — eddies forming patterns that resemble two figures reaching for one another.

Tour guides call it the January Embrace.

Scientists call it coincidence.

Locals call it penance.

The legend says that Eleanora walks the riverbank searching for Thomas, calling his name across the dark water. Some say that if you listen closely — between the fall of one wave and the rise of the next — you can hear him answer.

The Letters That Wouldn’t Burn

In 1898, a letter signed “E.T.H.” — almost certainly Elizabeth Thomas Harrison — surfaced in the archives of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. It reads:

“My mother chose the water in the end, believing it would reunite her with what she had lost. I have chosen instead to live, to teach, to create the world they imagined together. Some nights I dream of them walking along a distant shore, finally free.”

Her words confirm what history tried to erase: the love between the judge’s daughter and the enslaved man her family condemned.

The Missing Artifacts

In 1982, work crews renovating Charleston’s harbor discovered a sealed wooden box beneath the remains of old waterfront homes. Inside: a man’s gold ring and a water-damaged scrap of paper. Only one phrase could be read:

“Promised we would be free together…”

The box vanished from museum storage before it could be displayed.

Two decades later, in 2003, ground-penetrating radar at the old Whitmore site detected several unmarked graves near the river. The landowner refused excavation. Development proceeded. The report quietly filed the findings under “anomalies.”

The River Remembers

Today, the Whitmore name survives only on street signs and legal trusts. The plantation house is gone, replaced by modern homes. Yet even now, local historians speak of the unease surrounding that stretch of riverbank — a heaviness in the air, the faint scent of magnolia and brine.

One Charleston maintenance worker, interviewed in the 1990s, claimed to have found something carved into the underside of the balcony from which Eleanora “fell.” He described two names — Eleanor and Thomas — with the date January 23 scratched beneath, later gouged out as if someone had tried to erase it. The beam was removed and destroyed soon after.

The Final Entry

The last page of Eleanora Whitmore’s diary, before it too vanished, contained only a single line repeated over and over, her handwriting unraveling into panic:

“He returns each night. The river cannot hold him.”

And below it, written in darker ink, perhaps by another hand:

“I will join him soon.”

The River’s Verdict

Nearly two centuries later, the story of Eleanora Whitmore and Thomas Avery exists somewhere between documented history and ghost story — a love forbidden by law, destroyed by power, and buried beneath the currents of the Savannah River.

Some betrayals, the old people say, leave marks that even time and tide cannot erase.

And every January, when the night is still and the water runs high, someone leaves a small bouquet of white camellias and river reeds on the banks where the Whitmore house once stood.

No one has ever seen who leaves them.

But the ribbon binding the stems is always black.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load