The Most Disturbing Slave Mystery in Baton Rouge History (1848) | HO!!

A Carriage by the River

On the humid morning of August 23, 1848, a Baton Rouge merchant named Richard Caldwell stumbled upon an abandoned carriage by the muddy eastern banks of the Mississippi River. Its wheel was half-sunk in the riverbank; its doors hung open like a mouth that had forgotten how to close.

Inside lay only a man’s glove, an empty silver locket, and a leather ledger with no entries. The insignia engraved on the carriage door read Witmore Plantation—one of the largest estates east of Baton Rouge.

By noon, Caldwell’s discovery was in the hands of Constable James Harrington, who noted something odd: no one had seen the Witmore family in nearly three weeks. This in itself wasn’t alarming—planters often stayed on their estates during harvest season—but Samuel Witmore was known for one thing above all: punctuality.

For years, he had visited the First Bank of Baton Rouge every Thursday, without fail. But bank ledgers revealed three missed appointments. No word sent. No messenger.

When Harrington’s deputies rode out to the plantation that same afternoon, they expected illness, perhaps a family retreat. What they found instead became the foundation of the most disturbing and suppressed mystery in Louisiana’s history.

The Vanished Family

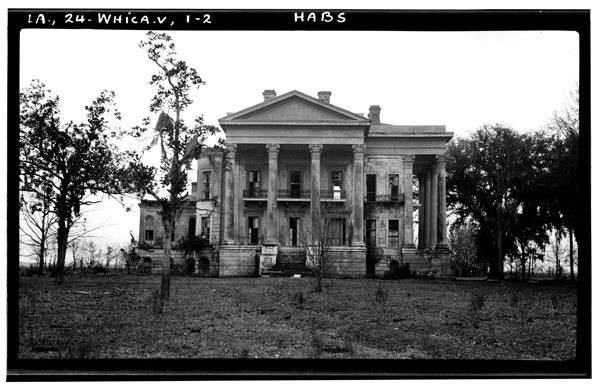

The plantation appeared untouched. Fields thrummed with labor; the enslaved workers continued their routines. Meals had been prepared, beds made, laundry folded. The great house stood immaculate—except for one thing.

The entire Witmore family was gone.

Samuel, 46.

His wife, Elizabeth, 42.

Their children, Thomas (23), Catherine (20), and William (18).

None were found on the property. None were seen leaving.

The only person out of place was Adeline Brousard, a house slave in her early thirties, described by witnesses as “quiet, obedient, and refined in speech.”

When questioned, every servant gave the same answer, word for word:

“Master Witmore has gone to visit his brother in Natchez. He will return before harvest.”

But Samuel Witmore had no brother—in Natchez or anywhere else.

The deputies left uneasy, their report strangely restrained. Yet within days, something darker began to take hold—a silence that spread through Baton Rouge like fog.

A Conspiracy of Silence

By October 1848, Judge Martin Lambert, a respected local magistrate and former business partner of Witmore, quietly opened a private inquiry. His notes, later discovered in a descendant’s attic, recorded what he called “the strange stillness surrounding the matter.”

“It is not merely that the family has disappeared,” Lambert wrote. “It is that no one wishes to speak of it. As if all have agreed to look away.”

Indeed, the plantation continued to operate. Cotton was shipped. Profits deposited at the bank—under signatures matching Witmore’s hand.

But in the house, servants whispered that Adeline Brousard had moved into the master bedroom. She wore Mrs. Witmore’s jewelry, spoke in her voice, and gave orders in the same calm, clipped tone.

A field hand named Moses told Lambert privately, “There ain’t no Witmores no more. Miss Adeline says there never was.”

Days later, Moses disappeared. The overseer claimed he “escaped.” None believed it.

The Dinner That Changed Everything

The following February, a daguerreotype was taken during a gathering of neighboring plantation owners—a formal dinner at the Witmore estate.

When the image resurfaced in 1931, historians were stunned. At the head of the table sat a Black woman in fine silk, her hair coiffed, her posture regal. Every white guest around her smiled, raised glasses, and looked utterly at ease.

The woman was Adeline Brousard.

Dr. Harold Bennett of Tulane University analyzed the image in 1934, writing,

“The expressions betray no awareness of impropriety. The guests behave as though the woman presiding is indeed Mrs. Witmore.”

It was as if the entire plantation class had entered into an unspoken pact—to pretend that nothing was wrong.

The Night of August 1st

The truth, or something close to it, emerged years later.

In 1865, after the Civil War, a former slave named Isaiah Cooper gave a statement to a Union officer investigating plantation abuses. His words, preserved in military archives, described that fateful night of August 1, 1848:

“Master Witmore, he had a cruelty that didn’t show on the skin. Miss Adeline, she suffered more than most. One night, she made supper for the family—fine meal, wine and all. They was laughing when the coughing started.”

“They grabbed their throats, eyes bulging. Master looked at her like he finally understood. She sat still as stone.”

According to Cooper, Adeline poisoned the Witmores at dinner, then gathered the house servants. Calmly, she announced that the family had gone to visit relatives in Natchez and that she would manage the estate in their absence.

“And here’s the strangest part,” Cooper said. “Everyone nodded. Like that was perfectly normal. Like we hadn’t just seen what we seen.”

That night, under her direction, several men buried the bodies deep in the swamp on the eastern edge of the plantation. The next morning, Adeline resumed her duties—now as mistress of the house.

The World That Chose Not to See

What followed was something no historian can fully explain.

Neighbors called, dined, and conversed with Adeline as if she truly were Elizabeth Witmore. The illusion—or collusion—spread. Baton Rouge society, both white and enslaved, participated in a shared fiction.

Judge Lambert, in his final writings before his forced removal from the bench in 1849, summarized it chillingly:

“They cannot acknowledge what has happened without confronting what preceded it. And that, it seems, is the one truth they cannot bear.”

He was later declared mentally unstable, his house vandalized, his notes confiscated. He died three years later in New Orleans, still writing about “the silence that swallowed reason.”

Becoming Mrs. White

In 1866, after emancipation, property records show that the Witmore estate was transferred to one “Mrs. Adelaide White — a free woman of color.”

The name was new. The handwriting was not.

Bank records revealed that for years following the disappearance, transactions continued—small cash withdrawals, payments for French books, jewelry, fine dresses, and even freedom papers for three enslaved individuals.

The plantation’s profits, once built on bondage, were being used to purchase liberty.

By 1870, “Adelaide White” appeared in census records as a widowed landowner. Locals described her as “a woman of learning and strange calm, respected by both black and white alike.”

She lived quietly, running a modest farm, treating neighbors with herbal medicine, and funding small loans to freed families.

A Photograph, a Face, a Legacy

In 1948, a daguerreotype surfaced from the descendants of a nearby family. It depicted an elderly Black woman, plainly dressed, seated on the porch of a farmhouse. On the back, in faint ink:

“Madame White — healer, landowner, once of the Witmore place.”

If true, it was the final image of Adeline Brousard—the enslaved woman who had become the mistress of the estate she once served.

Her gravestone, marked Adelaide White (1833–1882), was lost during the relocation of Highland Cemetery in 1959. Her resting place is now unmarked, paved over by modern Baton Rouge.

The Letters That Shouldn’t Exist

In 1968, a discovery in a New Orleans attic added another haunting layer. Among a bundle of 19th-century correspondence were letters from Elizabeth Witmore’s sister, Caroline Beaumont, written between 1848 and 1849.

Her September letter read:

“I have received no word from Elizabeth. The maid Adeline insists the family is away, but her manner chills me. She speaks as Elizabeth might, with the same turns of phrase. When I asked when they’d return, she smiled and said, ‘They are never coming back, but we need not speak of that.’”

By March, Caroline wrote again:

“I am unwelcome here. They all pretend nothing is amiss. Even Judge Lambert now urges silence. I begin to question my own sanity.”

She fled Louisiana soon after.

The Science of Denial

A century later, psychologist Dr. Katherine Monroe analyzed the case, describing it as “a rare instance of collective dissociation.”

“When reality threatens the very framework of society,” she wrote, “people reframe the impossible into the acceptable. It is easier to maintain a lie than rebuild the world.”

Indeed, the community’s reaction—its willingness to treat Adeline as Mrs. Witmore—was less delusion than survival. To confront the truth would have meant facing the rot beneath their entire social order.

What Remains

By 1962, when highway construction unearthed five skeletons—two men, one woman, and two youths—on the former Witmore grounds, few bothered to ask who they were. The bones were quietly reburied in an unmarked grave.

Today, Interstate 10 runs directly over their resting place. Thousands cross it each day, unaware that beneath their tires lies the burial ground of a family erased by their own society’s denial.

No marker. No memorial. Only the hum of engines and the silence of history.

What We Choose Not to See

The story of Adeline Brousard is not only one of murder—it is a mirror.

It reveals how an entire community can conspire in blindness, how horror can be normalized through the sheer will to maintain order. In Judge Lambert’s last journal entry, dated January 18, 1852, he wrote:

“What frightens me most is not that such things can happen, but that we can look directly at them and see nothing at all.”

More than a century later, Dr. Eleanor Pritchard echoed the same sentiment when her 1965 manuscript on the case was rejected by every publisher she approached:

“The Witmore affair is not about slavery or murder alone. It is about human vision—the things we cannot, or will not, see.”

And so Baton Rouge grew up and over its own graveyard of truths. Shoppers park where the main house once stood. Children play where bones once lay.

But stories, like bodies, do not stay buried forever.

They rise after heavy rain.

They whisper through time.

And they remind us that the most terrifying horrors are not supernatural—but human.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load