The Mistress Who Fell in Love with a Slave — and Planned Her Husband’s Death to Start a New Life | HO

In the blistering summer of 1863, as the Civil War scorched its way through the American South, the quiet hills of Whitfield County, Georgia, witnessed a story so shocking, so intimate in its horror and courage, that it still lingers like a ghost on the land where it unfolded.

It began as an ordinary domestic tragedy — a cruel husband’s disappearance, a lonely wife’s sudden freedom. But beneath that surface of Southern respectability simmered a secret: forbidden love, murder, and an escape so daring it would echo across generations.

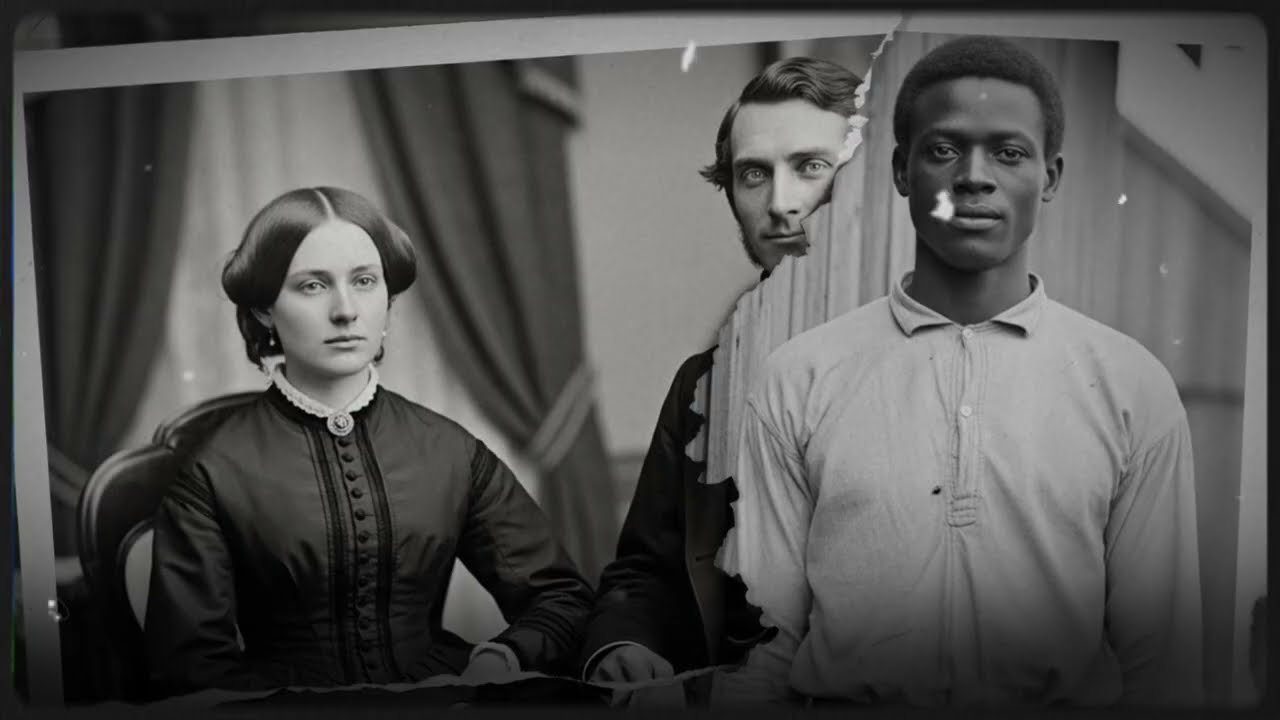

This is the story of Arabella Patterson, the mistress who fell in love with her husband’s slave — and planned his death to win their freedom.

The House of Fear

The Patterson property was modest — fifty acres of cotton, corn, and cruelty. It belonged to Kellen Patterson, a man whose reputation for violence was as wide as his fields. At forty-one, he was a drinker, a brawler, and, in the eyes of neighbors, “a man you didn’t cross unless you had a death wish.”

He inherited the land from his father, along with two slaves: Vera, an older woman whose silence was her armor, and Levi, a young, strong field hand bought at auction in Augusta. From the first day, Kellen ruled by fear. His wife, Arabella, had arrived in 1860 — a bride sold by her struggling family to secure their debts.

She was twenty-six, pale and soft-spoken, with eyes that hinted at the intelligence she was forbidden to use. Her marriage to Kellen was a transaction, not a union. Within weeks, she learned that her new home was a prison.

Neighbors heard screams at night. They whispered but never intervened. In that era, a man’s home was his kingdom, and a wife’s suffering was his private right.

A Slave, a Mistress, and a Dangerous Kindness

Of all the torments that defined Arabella’s new life, one figure quietly defied Kellen’s darkness: Levi. He worked the fields by day and endured the same lashings, the same humiliations that defined the Patterson farm.

Over time, shared suffering became silent understanding. Arabella began finding reasons to linger near the barn — to ask about the crops, to bring water, to speak, even briefly, with someone who didn’t treat her as a possession.

Her diary — later found by investigators — described that turning point:

“He looked at me as though I were human, not property. When he speaks, I feel I exist again. I know it is dangerous to feel this way. But I am no longer afraid.”

Their connection deepened into something both miraculous and doomed. To love across the lines of race and slavery was a crime that could mean death for them both. Yet, as months turned into years, that secret love grew stronger than their fear.

Then came the pregnancy.

In June of 1863, Arabella discovered she was expecting a child — Levi’s child. And with that realization came terror. “When Kellen finds out,” she wrote, “he will kill us both.”

The Plan

For weeks, they whispered in the shadows, searching for a way out. Running was impossible while Kellen lived. The war raged beyond their fields, but inside their small world, there was only one path to freedom: Kellen had to die.

Levi, who had learned the secrets of the forest to survive hunger under previous masters, knew which plants could kill slowly. Together, they gathered water hemlock and poisonous mushrooms, drying and grinding them to powder.

The plan was simple but meticulous. Small doses in Kellen’s morning coffee — just enough to mimic a summer fever. By the time he died, it would look like natural illness.

Arabella forged a letter of “abandonment,” practicing her husband’s handwriting for weeks. The letter claimed Kellen had left to enlist in the Confederate army, seeking honor in war. It even included stains — smudged ink and false tears — to appear authentic.

A drifter in debt, promised $50, would ride down the road the night of their staged disappearance, ensuring that neighbors saw “Kellen” leaving the property.

Everything was set.

But on the night of July 13, 1863, everything changed.

The Night of Fire and Blood

According to Arabella’s final diary entries — written in a trembling hand — Kellen came home drunker and more violent than ever. He had lost money gambling and had been mocked for avoiding the war.

He stormed into her room after midnight, reeking of whiskey and rage. “He said he was tired of my face,” she wrote. “He said it was time to clean house.”

He began strangling her.

Downstairs, Levi heard the struggle. For years, he had learned to stay silent during Kellen’s rages. But this time, he ran.

Vera, awake in the kitchen, saw him sprint toward the house “like a man possessed.” Moments later, the walls shook with the sounds of violence — shouts, furniture breaking, gasps. Then silence.

When the noise stopped, Kellen Patterson was dead. Levi had strangled him — not in cold blood, but in desperate defense. Arabella, half-conscious, woke to see her husband’s lifeless face on the floor.

What followed was grim, deliberate survival. Before dawn, they buried Kellen in the south field beneath a large oak, six feet deep. Arabella burned his clothes and washed the blood from the floor.

At sunrise, the letter of enlistment was placed neatly on the kitchen table. The man they hired rode by, and the neighbors — the Morrisons — saw him from afar, thinking Kellen was leaving for war.

By morning, the monster was gone.

Freedom’s Price

Sheriff William Hayes, the aging county lawman, led the investigation. In wartime Georgia, missing men were nothing new. The letter looked genuine, the story plausible. Kellen Patterson, they concluded, had abandoned his wife to join the Confederate army.

Arabella played her part flawlessly — shocked, trembling, but quietly composed. Within weeks, she ran the property herself, kind to Vera and Levi, diligent with the fields. Neighbors called her “a woman transformed.”

But transformation takes many forms. In private, she was selling jewelry and valuables, converting everything to gold coins. She visited merchants in Dalton and Marietta, each time offering a small piece of her past — a ring, a brooch — and buying a bit more of her future.

Four months later, on a cold November night, Arabella and Levi vanished.

Vera, left behind, told neighbors that Arabella had received word of her husband’s death in battle. But no letters had come. The story didn’t hold.

When Sheriff Hayes searched the house, he found Arabella’s diary — hidden, but not too well hidden. It was as if she had wanted it found.

The diary told the whole story: the abuse, the poison plot, the murder that became self-defense, and the plan to flee north to Cincinnati — or so it claimed.

Hayes suspected otherwise. “No woman that clever would leave her true destination in writing,” he noted in his journal. “Cincinnati was a decoy.”

Vera’s Confession

Five years later, in 1868, Hayes got his final answer.

In Savannah, Vera lay dying, her body frail but her mind sharp. She had carried the secret for years and now wanted peace. “They never spoke of Cincinnati,” she whispered. “They spoke of the West.”

Vera revealed how she had seen the struggle that night, how Levi had run into the house knowing it would cost him his life, and how Arabella had helped bury the body without a single tear.

“She was calm,” Vera said. “Calm like someone who’d been waiting her whole life for that night.”

Arabella and Levi had spoken of places where “no one asked questions” — Colorado, Nevada, the mining towns where new names meant new lives. They’d met people who helped fugitives escape through the chaos of war — the same underground networks that aided enslaved people fleeing north.

Vera watched them leave on a moonless night. Arabella hugged her, whispering, “Forgive me.”

“There was nothing to forgive,” Vera told her. “You did what anyone would do to survive.”

Vera died three days later, her confession written in Hayes’s notebook.

The Legend of the Patterson Property

The story of Arabella and Levi became local legend — part history, part haunting. The Patterson property was sold, then abandoned. Workers who camped there claimed to hear whispers in the night and dreamed of a woman’s cry echoing through the trees.

By Reconstruction, it was known as “the cursed farm.” The oak in the south field still stood, its roots tangled in the grave of a tyrant.

For Sheriff Hayes, the case remained open — not as a crime, but as a question. In his old age, he called it “the most justified murder I ever investigated.”

“They killed a man who deserved to die,” he told visitors. “They saved a life — two lives. And then they vanished. That’s justice enough for me.”

The Disappearance That Became Deliverance

To this day, no one knows what became of Arabella Patterson and Levi.

Some say they reached Colorado, blending into the flood of miners and settlers who poured west after the war. Others imagine they crossed into Canada, living freely as husband and wife under new names.

Whatever their fate, they succeeded in the impossible: they disappeared.

Their story endures not as a tale of murder, but of deliverance — a testament to what love and desperation can drive ordinary people to do. Arabella’s diary, now lost to time, captured it best:

“We did not seek revenge. We sought life. And life demanded a terrible price.”

A Love Beyond Chains

In the century and a half since that fateful summer, historians have argued over the morality of what happened at the Patterson property. Was it murder? Self-defense? Rebellion?

Perhaps it was all three.

Arabella’s act was both crime and liberation — a desperate woman’s refusal to be silenced, and a slave’s triumph over his oppressor. Their union defied the laws of their time, but in doing so, they embodied something more timeless: the human need for freedom, love, and dignity.

Today, the Patterson ruins are almost gone — the farmhouse swallowed by vines, the fields reclaimed by the earth. But the great oak still stands, its branches whispering in the Georgia wind. Beneath it lies the man whose cruelty ended in justice, and above it lives the legend of two souls who chose love over fear.

Their story reminds us that freedom is not always given — sometimes, it’s taken.

And sometimes, the most beautiful endings are not the ones written in court records or history books, but the ones that vanish into the sunset — two figures riding west, finally free.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load