The Georgia Sisters Who Bought the Slave for Forbidden Practices… Until Both Got Pregnant | HO

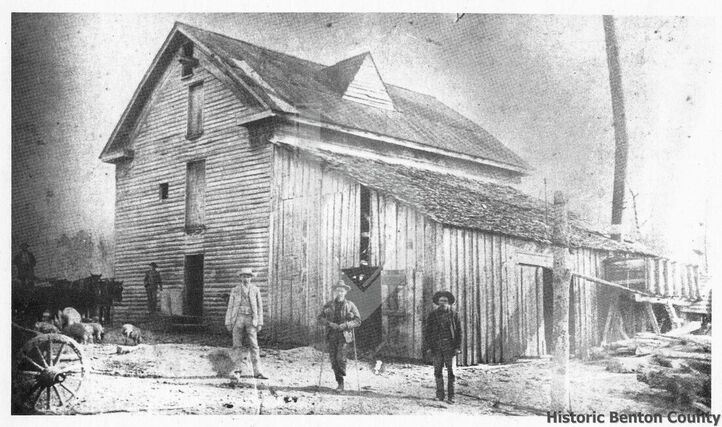

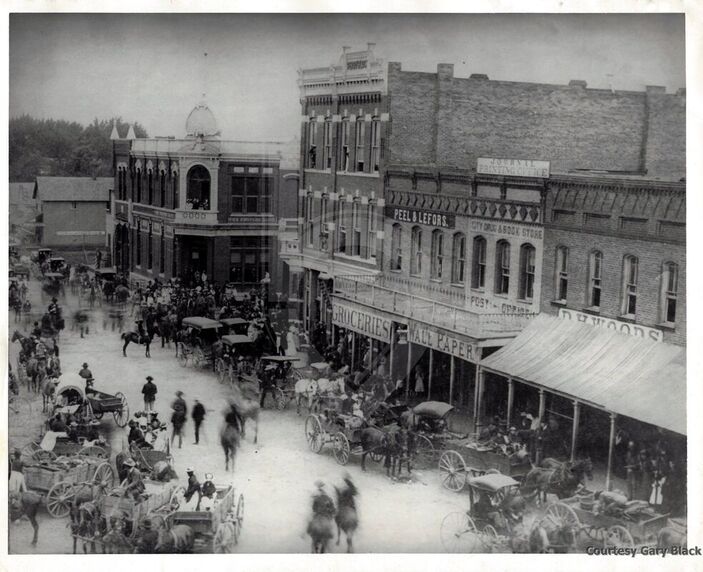

It began in 1844, in Benton County, Georgia, on an estate called Harcourt Plantation—three miles east of Whitesburg. The property, framed by rolling hills and pine forests that seemed to swallow every sound, belonged to two sisters: Amelia and Charlotte Harcourt.

In local memory, their names are still whispered—sometimes with pity, more often with dread.

The Inheritance

The Harcourt sisters inherited the plantation after a tragedy. In 1841, their parents perished in a carriage accident on the road to Atlanta, leaving the young women—both unmarried, both in their twenties—in control of more than 800 acres of fertile cotton fields and the 37 enslaved people who worked them.

For a time, the sisters ran the estate efficiently, even admirably. County ledgers from the 1840s show the Harcourt plantation producing above-average yields. They entertained guests, attended church, and kept their accounts in impeccable order.

But in late 1843, something changed.

Records uncovered during courthouse renovations in 1962 revealed a string of unusual transactions—chief among them, a purchase made by Amelia Harcourt during a trip to the Savannah slave markets that December.

She bought a man named Elijah Brooks—25 years old, literate, and described as “exceptionally intelligent.” What puzzled historians was the note attached to the sale:

“Buyer insistent on this particular individual despite numerous others available.”

Dr. Margaret Wells, who studied antebellum plantation records in the 1950s, called it “anomalous.” Women of the planter class rarely purchased enslaved men alone, much less at a premium price. “Her insistence,” Wells wrote, “suggests prior correspondence or purpose.”

Whatever that purpose was, its results would soon become infamous.

The Pregnancies

Six months after Elijah’s arrival, the plantation physician Dr. Samuel Thorne began receiving unusual summonses.

In his journal—discovered in 1961—his entries grow increasingly distressed.

April 12, 1844:

“Attended Miss Charlotte Harcourt. Symptoms confirm pregnancy, ten weeks. Patient hysterical. Sister Amelia calm, unnervingly so.”

May 23, 1844:

“Miss Amelia now also pregnant, approximately twelve weeks. Both refuse to name the father. The house thick with unease.”

June 18, 1844:

“Summoned urgently. Charlotte delirious—claims to hear voices through the floor. Amelia forbids examination. Offered discreet removal to Atlanta. Denied. I fear for their sanity.”

That was Thorne’s final entry. He was never again called to Harcourt Plantation.

Whispers in the Fields

That summer, Benton County suffered a devastating drought. Crops withered across Georgia’s western counties—except on Harcourt land.

Neighbor Thomas Blackwood wrote to his brother:

“Our cotton burns in the sun, yet their fields remain green. They claim new irrigation methods, but the workers refuse to speak of them. Their eyes are strange. The place feels… wrong.”

By autumn, the sisters had withdrawn from public life. They stopped attending church. The workers no longer visited neighboring plantations. The Harcourt property, once a symbol of prosperity, became a place people crossed the road to avoid.

And yet, behind those shuttered windows, something was happening. Something that witnesses would describe decades later in whispers and trembling tones.

“They Drank from the Soil”

In 1872, an elderly woman named Josephine Miller, a former house servant, gave an interview to Reconstruction officials. Her recollections—now preserved in the state archives—were chilling.

“Miss Amelia and Miss Charlotte would sit in the cellar with candles burning black smoke. Mr. Elijah read from books with strange letters. They had us bring soil from all over the plantation, mix it with things I won’t speak of. Then they’d drink it.”

Josephine claimed the sisters believed the children they carried would be “born of the land itself.”

By late autumn, half the plantation’s enslaved workers had fled into the woods.

The Fire

On November 12, 1844, Reverend James Wilson of White Oak Baptist Church received a desperate letter from Charlotte Harcourt begging for spiritual aid. When he arrived, the house was in disarray—windows blackened, symbols carved into doorframes, and the air “thick with a foul odor.”

Charlotte, pale and trembling, told him:

“We are preparing the soil for what is to come.”

Elijah Brooks was nowhere to be found.

Three days later, one of the cotton barns went up in flames. Blackwood and several neighbors rushed to help. What they saw unsettled them for life.

“The workers made no move to stop the blaze,” Blackwood wrote. “They chanted softly, eyes fixed on the fire. Amelia stood in the upstairs window, unmoving. Charlotte was led past the glass by a man’s shadow. Both were heavy with child.”

The smell, he said, was “not just wood or cotton—but something else. Something alive.”

The Night of December 15

Winter came early that year. On a moonless night in mid-December, neighbors heard unearthly wailing from the Harcourt property. The sounds—neither fully human nor animal—rose and fell for nearly an hour before ceasing abruptly.

At dawn, smoke curled above the plantation.

The east wing of the house was burned to ruins. In a surviving bedroom, investigators found bloodstained sheets and evidence of childbirth—but no infants.

Neither Amelia nor Charlotte was ever seen again. Nor was Elijah Brooks.

The official report concluded simply:

“Evidence of unorthodox practices. No remains recovered. Case closed.”

The Land Remembers

For decades, the story faded into rumor—until 1959, when construction crews building a new highway through Benton County unearthed a small wooden box six feet underground.

Inside were two silver lockets, each containing braided hair—one fair, one dark—and a folded sheet of parchment written in an unrecognizable language.

The artifacts were sent to the Georgia Historical Society, where they mysteriously vanished from the archives within a few years.

The researcher who had examined them, Dr. Alan Carmichael, resigned shortly afterward and disappeared during a field trip to the Harcourt site in 1968. In his recovered notes he wrote:

“The sisters sought to create vessels—offspring that could anchor something ancient in the soil itself. They were not dabbling in superstition. They were merging with it.”

His car was later found abandoned near the former Harcourt property line.

Echoes Beneath the Reservoir

In the 1960s, part of the old plantation was flooded to create a reservoir. During excavation, workers discovered a circular stone chamber beneath the soil—its walls inscribed with the same symbols Reverend Wilson had described a century earlier.

Tests revealed the stone was not native to Georgia—but to West Africa. In the chamber’s basins were traces of human blood from three distinct genetic types, preserved through some unknown means.

Dr. William Harper, who led the dig, died two weeks later of a stroke. His final note read:

“They were here before us. They used the sisters. They are still here.”

A Legacy in the Blood

In 1952, an Emory graduate student named Rebecca Collins uncovered a strange pattern in early 20th-century birth certificates: a notation reading “Heritage: Harcourt Descent.”

The children so marked—many from mixed-race families—shared an unusual trait: a birthmark of interlocked circles on the left shoulder.

One descendant, Sarah Turner, showed Collins a small silver amulet containing soil and braided hair. “Every family with our blood buries one,” she said. “So the earth remembers its children.”

Collins included only a single cryptic footnote in her dissertation. Years later, when asked why, she replied, “Some knowledge isn’t meant for publication.”

The Forbidden Fertility

Throughout the 20th century, farms within 50 miles of the old Harcourt estate continued to thrive during droughts when others failed. Scientists blamed irrigation. Locals blamed something older.

An agricultural agent’s private journal from 1956 describes midnight gatherings of mixed families—white and Black—burying bundles of hair, blood, and soil at the corners of their fields.

They called it “feeding the land.”

When asked about it, an elderly woman only smiled and said, “The sisters taught us. We just keep it going.”

The Modern Descendants

In 1998, anthropologist Dr. Lydia Montgomery met with self-identified descendants of the Harcourt sisters and Elijah Brooks. They all bore the same interlocked-circle mark. They claimed their fertility—both of soil and body—was sustained through rituals held every 150 years, the next due that December.

Montgomery’s final diary entry read:

“They call it the Sesquicentennial Returning. The dreams won’t stop. The sisters speaking through the soil. They want to be born again.”

She resigned from her university within days and vanished from public life.

What the Soil Holds

In 2011, drought lowered the reservoir, revealing the buried stone chamber once more. Locals entered before authorities sealed it. All five were found unconscious but unharmed.

One, Joshua Turner, later wrote:

“I saw them—Amelia, Charlotte, Elijah. Not separate beings, but one consciousness spread through the land. Their bodies dissolved, but their will remains. They whisper that the next generation is nearly ready.”

Turner disappeared in 2019. His garden, found weeks later, bloomed wildly despite weeks without rain. Soil tests showed genetic material from dozens of individuals—preserved, alive.

The Land That Breathes

Today, the Harcourt name is buried beneath subdivisions and highways. The plantation itself lies beneath a lake. But some say the legacy still breathes through the land.

Farmers nearby still report impossible fertility. Families with the circle birthmark still whisper about “the old ways.” And late at night, if you stand on certain patches of dark, rich soil, you may feel a faint vibration beneath your feet—as if something vast and patient were stirring just below.

The story of the Georgia sisters who bought a man for forbidden practices is not just a tale of scandal and tragedy. It’s a warning about what happens when blood and earth are bound together for purposes no one fully understands.

Because the Harcourt sisters may be long gone—but whatever they awakened in that soil has never gone back to sleep.

And the land, as the locals still say, remembers everything.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load