The Enslaved Midwife Who P0is0ned Her Mistress’s Bloodline Charleston’s Hidden Curse of 1844 | HO!!!!

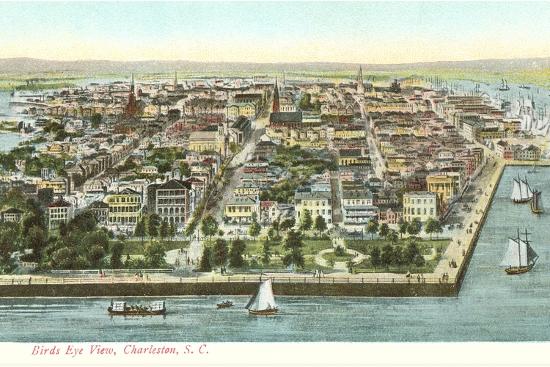

In the humid summer of 1844, somewhere north of Charleston, South Carolina, a legacy of pride, wealth and privilege stood quietly among the live-oaks and Spanish moss.

But beneath that polished surface a quieter, darker vengeance was unfolding—one that would not crackle with gunfire or blaze in the night sky, but seep slowly, inexorably, through the veins of a family, until it reached the root of life itself.

The estate belonged to the Rutled family: four generations of rice planters, wealthy through land and enslaved labour. Their great house, perched three miles north of Charleston, looked out over the Cooper River and the shipping lanes that fed the city’s commerce.

At its centre stood William Harrison Rutled, a prominent attorney, who had inherited the plantation in his mid-twenties and expanded it with business savvy and family connections. His bride, Sarah Elizabeth Baker, came from Charleston’s oldest society; their 1835 marriage was celebrated with grandeur, uniting two elite lines.

By all appearances the Rutleds were the very image of antebellum success: a stately home, sprawling fields, a household staff of more than seventy enslaved people. Among them were the usual domestic attendants, stablemasters and nurses—but one woman among them held an unusual position.

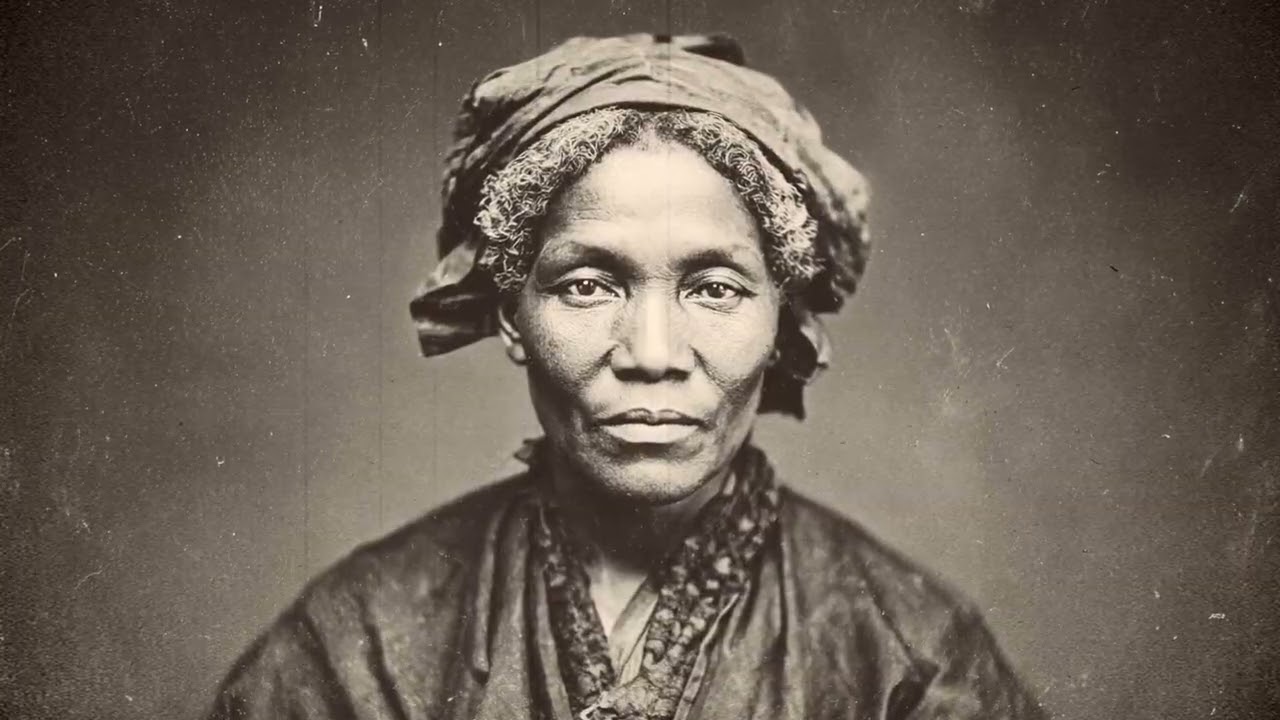

Her name was Rebecca. Born into slavery on the Rutled plantation some forty years earlier, she served the family as midwife, healer and trusted attendant. She delivered William himself as a child, assisted his siblings, and in 1844 brought into the world his third child with Sarah.

Yet as the summer sun rose to its high point in 1844, Sarah Elizabeth fell ill. At first it was subtle: fatigue, headaches, occasional stomach pain. In a house used to managing its affairs of status and commerce, the explanation was easy—post-partum strain, heat, a few bad peaches.

But the symptoms grew peculiar. By May, Sarah was pale, thin, weak; by June she was confined to her bed, unable to rise except with assistance. Dr. Edward Thompson, the family physician, prescribed tonics of iron and quinine, believed it malaria or the lingering effect of childbirth. But the treatments failed, and in fact, seemed to hasten the decline.

All the while Rebecca moved quietly through the house, preparing teas, mixing poultices in her little garden behind the kitchen quarters. She was always nearby when Dr. Thompson met William. She was always present when the children’s nurse delivered the morning water and fresh linens to Sarah’s room.

In a household that treated its enslaved staff as silent fixtures, Rebecca’s presence went unremarked. Until one morning in late July, Sarah died in the bed she had once managed with grace and authority. She was just twenty-nine.

The official cause of death: “wasting illness of unknown origin.” The funeral at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church drew the city’s elite. Life resumed. William returned to his work. The children were cared for by their nurse. The plantation slipped back into habit and routine.

Then William himself became ill. In late August, he complained of nausea, cramps, weakness. By September he was bedridden in the same room where his wife had perished only weeks earlier—skin yellowed, strength gone. Dr. Thompson was worried: the pattern mirrored Sarah’s illness yet no one else in the household had become sick. No fever epidemic. No mass infection. Something targeted—and methodical.

Suspicion first fell upon Rebecca when one of the younger attendants, Martha, noticed a pattern. She reported quietly to the stable-master Richard: Rebecca carried a small cloth pouch, she added powder to the master’s tea, she harvested roots unfamiliar to the kitchen garden. At first Richard dismissed it—Rebecca had long served the family. But Martha persisted. Under observation they saw Rebecca mixing a greyish powder into William’s cup and seldom enough in baby James’s feeding milk as well.

When Mary, the eldest house-servant, joined their secret counsel, she revealed the hidden motive. Years earlier Rebecca’s daughter—a child of Rebecca’s whose father was William’s father—had been born on the plantation, fair-skinned and green-eyed, and sold at age three to a Georgia plantation. Rebecca’s secret grief had never healed. Mary said Rebecca had waited decades for the “perfect moment” to extract vengeance on the Rutled and Baker families who she held responsible.

One night, they searched Rebecca’s tiny cabin, found hidden pouches of powders, dried roots, and a journal in Wolof and English detailing the progressive symptoms of arsenic poisoning and the decline of Sarah and William. Found also a lock of light brown hair tied with blue ribbon—Rebecca’s daughter’s hair. The evidence was taken to Dr. Thompson who confirmed toxins typical of arsenic and other plant derived poisons.

Rebecca’s arrest followed. Her trial in October 1844 became Charleston’s most sensational antebellum legal event. Without representation—typical for enslaved defendants—she listened as the physician, attendants and servants testified. Her final words recorded: “I brought them into this world. It was fitting that I should usher them out. What was taken from me cannot be restored. What I have taken cannot be undone. There is a balance in all things.”

The jury deliberated less than an hour. On November 2, 1844, Rebecca was publicly hanged—the first female slave executed in the city for poisoning a white master’s family.

William survived, though weakened, and died in 1855 at age forty-six. The children lived on: Thomas left the plantation in 1871, Catherine moved north, James became a physician specializing in toxicology. The plantation itself vanished: the grand house burned in 1894; the land quietly reverted to forest and underbrush. Rebecca’s cabin remains unmarked; her grave unknown.

The case loosened the veneer of the plantation household. Archival work in 1965 uncovered what had been buried: in the soil of the former garden, archaeologists found years of cultivated poison-plants, a carved African symbol of justice placed circa 1825, an infant grave by the cabin.

In 2011 new documents emerged—Mary’s post-humous account revealing further implications of Rebecca’s plan to erase entire bloodlines. But no full justice was ever paid. The system that enslaved Rebecca also silenced her, serving the power of property rather than personhood.

How many other voices lie unheard beneath the oak shadows of the Low Country? How many hidden resistances took the form of subtle sabotage, slow death, quiet uprising?

For visitors in Charleston today, the storied facades and guided tours of Magnolia Cemetery or St. Michael’s speak of wealth and tradition—but seldom of the invisible midwife who poisoned the bloodline of her mistress.

No plaque marks Rebecca’s cabin, no tour bus stops at the garden where the herbs grew. The bronze plaque at Magnolia Cemetery inscribed for Sarah Elizabeth indicates her years of life—and bears silent witness to what really transpired.

In telling this story, we do not comfort ourselves with simple narratives of heroism or vindication. We confront a system so corrupting that it warped every relationship it touched—between mistress and attendant, master and midwife, bloodline and betrayal. Rebecca is not easily cast as villain or victim. She is both—a human response to horrors that the law of her time would not, could not, remedy.

And so the story lingers: in the soil of the former plantation, in the faint scent of marshen herbs on new-moon nights, in the small glass vial discovered under a hidden wall. “There is a balance in all things,” she said. The ledger of history may be incomplete—but the debt has not yet been paid.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load