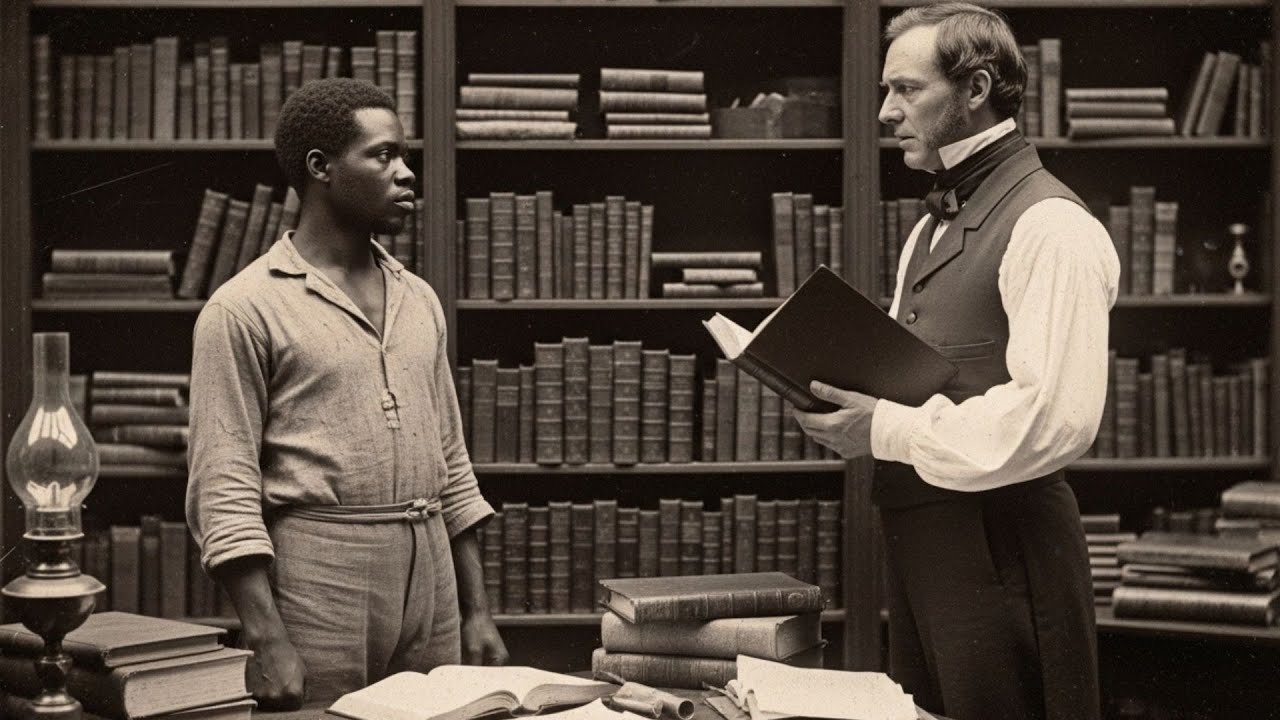

“I Translate This Bible For My Freedom”, the Master Mocked… but the Slave Read in Perfect Latin | HO!!

St. Charles Parish, Louisiana — The cypress trees still whisper along the slow bend of the Mississippi River. Beneath their heavy branches, the ground once held the grand house of Willow Creek Plantation, where in 1842 a fire devoured a library — and with it, the lives, secrets, and illusions of a family that believed knowledge could be owned.

What burned that summer night wasn’t only paper and wood. It was a system.

For over a century, the tragedy at Willow Creek existed only as rumor — an old tale of a “learned slave” and a “mad master” whose house went up in flames. But in the mid-20th century, archivists uncovered fragments that forced historians to confront one of the most unsettling episodes in Louisiana’s past: the story of Jacob, an enslaved man who read Latin with the fluency of a scholar, and Howard Turner, the plantation owner who tried to turn that knowledge into profit — until their battle of words ended in fire.

A Man Who Shouldn’t Have Known Latin

The first trace of Jacob’s name appears in a letter dated April 18, 1842, written by Reverend Samuel Witmore to his brother in Boston:

“A man they call Jacob, who they claim was taught nothing but fieldwork, demonstrated a knowledge of Latin that would shame most scholars at Harvard.”

The letter, found in a Massachusetts church attic in 1962, was dismissed at first as apocryphal. But parish purchase ledgers confirmed that in 1839, Turner had indeed bought a man called Jacob from a Virginia estate — listed simply as male, approximately twenty-five, field worker.

Within a year, household ledgers note: ‘Negro Jacob reassigned to house duties. Demonstrates unusual literacy.’

From that single entry, the descent began.

The Pact

Turner’s wife, Elizabeth, began keeping a private journal around the same time. Found behind a loose wall panel during renovations in 1958, her neat handwriting grows increasingly frantic over two years.

“Howard has taken an unusual interest in the new house servant,” she wrote in December 1840. “He spends evenings in his study with the man. I hear voices, sometimes raised, sometimes hushed.”

By 1841, her tone darkened.

“He keeps the library locked. He speaks of translations and divine inspiration. I fear this work will never be complete.”

Turner, who had never shown interest in scholarship, suddenly began ordering rare books — Latin Bibles, Roman histories, philosophical treatises. A merchant’s ledger from New Orleans records one such sale: “One Latin Bible, imported from Rome at great cost.”

Later evidence revealed that Turner had begun presenting translations of obscure Latin texts to scholarly societies — works that earned him brief acclaim and astonishment. The newspapers praised his intellect. None suspected that the mind behind those translations belonged to the man he owned.

The Slave Scholar

Martha Johnson, a house servant interviewed in 1923 at age ninety-two, recalled the extraordinary relationship:

“We thought Jacob’d be whipped when Mister Turner found out he could read. But instead, he brought him books. Asked him to read out loud words none of us could understand. Mister Turner would write while Jacob spoke.”

Turner’s ambition was simple — to use Jacob’s brilliance as a ladder to respectability. In return, he offered the one thing Jacob desired most: freedom.

The arrangement should have remained secret. But Elizabeth’s journal captured its corrosion.

“Howard speaks of manumission papers being drawn up,” she noted in September 1841. “Yet I fear the work will never be deemed complete.”

Over time, that fear became prophecy.

“I Translate This Bible for My Freedom”

The final entries in Elizabeth’s journal read like the buildup to an explosion.

June 1, 1842 — Howard has refused him again. I heard their voices through the door. Jacob spoke in Latin, calm and clear. He said, ‘I translate this Bible for my freedom.’ Howard laughed — said no amount of translation would ever be enough. Then Jacob answered something in Latin that made Howard grow pale.”

The next night, the library caught fire.

When parish officials sifted through the ashes, they found two bodies — one identified as Howard Turner, the other presumed to be Jacob. The case was declared an accident. No further investigation followed. In the antebellum South, the death of a master and a slave rarely warranted deeper inquiry.

But Elizabeth’s diary stopped abruptly on the very night of the blaze. And her actions after the fire — withdrawing large sums of gold, selling the plantation, fleeing to Charleston with her children — hinted at something far more deliberate.

Fragments in the Ashes

In 1957, an archaeological team from Tulane University unearthed a metal box in the ruins of the library. Inside were charred parchment scraps — Latin text written in two hands.

Professor Martin Cranwell, who examined the fragments, concluded:

“One writer wrestled with basic grammar. The other corrected him with masterful ease. It appears the enslaved man was teaching his master.”

Among the fragments was a haunting passage translated as:

“The master sees property where there stands a man. He cannot comprehend that knowledge exists beyond his permission. I wait. I translate. I buy my time.”

Those words, scholars agree, could only have come from Jacob.

Did Jacob Survive?

In 1959, historians cataloging Elizabeth Turner’s personal effects discovered a series of unsent letters. One, dated June 2 — the night of the fire, ends mid-sentence:

“He says the man knows too much. Imagine if others learned what one of them is capable of. Then he told me his plan to—”

The line breaks there.

A year later, a memoir by a Union soldier added a new twist. Writing in 1868, Daniel Foster described meeting an elderly Black man near the Mississippi border:

“He bore burn scars on his hands, taught Latin to freed children, and when asked about his past, he quoted Virgil in perfect form, then smiled.”

The man called himself the Professor.

Echoes of a Mind Unchained

Other clues surfaced across decades. A Louisiana church registry from 1870 lists a donor, “J.T., teacher of Latin and Greek, formerly of New Orleans.”

In 1965, workers demolishing a building in St. Francisville found a hidden room containing translation notes dated around 1860, written in alternating Latin and English. The manuscript, titled Memoirs of a Translated Man, begins:

“I was born twice. First to parents who gave me life but not liberty. Second to words on a page. In those words, I found a self that could not be owned.”

The document ends with a chilling sentence:

“Fiat justitia ruat caelum — let justice be done though the heavens fall.”

Ash was embedded in the paper fibers.

A Tunnel, a Church, a Name

Ground-penetrating radar at the Willow Creek site in 1967 revealed a narrow tunnel running from beneath the old library toward the riverbank — a possible escape route.

Two years later, renovation workers in Baton Rouge uncovered a small water-damaged book hidden inside a church pulpit. On its cover, the inscription read:

“Property of Jacob Turner Freeman, 1843.”

The handwriting matched the translations from Willow Creek. Inside, Jacob had written:

“I have walked through fire to claim what was always mine. My body bears its scars, but my mind remains unburned.”

And finally, the Latin phrase: Veritas vos liberabit — “The truth shall set you free.”

Knowledge as Rebellion

Historians now regard Jacob not as a legend, but as one of the most remarkable figures of intellectual resistance in the American South. Dr. James Washington’s 1968 study The Reader of Willow Creek described him as “a revolutionary of the mind.”

“Where others rebelled with force,” Washington wrote, “Jacob rebelled with knowledge. He proved that mastery of the oppressor’s language could dismantle the logic of oppression itself.”

In a society built on the belief that African Americans were intellectually inferior, the image of a man enslaved yet fluent in Latin — the sacred language of scholars, clergy, and power — was intolerable. For Turner, that knowledge was both opportunity and threat. For Jacob, it was salvation.

The plantation burned, but the ideas survived.

Fire, Freedom, and the Unwritten Legacy

Elizabeth Turner died in Charleston in 1864. Her will directed a donation “to educational endeavors among the formerly enslaved, in recognition that knowledge belongs to no master.”

Whether this was guilt, redemption, or both, no one can say.

Nothing remains of Willow Creek today. Its fields are paved over by warehouses, its grand house vanished beneath industrial soil. But the fragments endure — bits of Latin parchment, journal pages, unsent letters — evidence of a confrontation between two men trapped in a system that could not contain the power of thought.

Local folklore still speaks of the “man who read in perfect Latin.” Workers along the river claim that on windless nights, faint voices echo through the trees — ancient words carried by the humid air:

“Scientia potentia est.”

Knowledge is power.

The Fire That Never Went Out

Perhaps that is the truest horror of the Willow Creek case — not ghosts or curses, but what happens when knowledge itself becomes dangerous.

Howard Turner believed that by owning Jacob’s body, he owned his mind. Jacob proved him wrong. His mastery of Latin — the language of theology, law, and reason — exposed the lie at the heart of slavery: that intelligence and humanity were privileges reserved for the powerful.

In the end, both men were consumed — one by arrogance, the other by fire. Yet the survivor, if he truly lived, carried from that inferno something indestructible: an idea that words could break chains more effectively than any weapon.

More than 180 years later, Jacob’s story reminds us that revolutions do not always begin with battles. Sometimes, they begin with a man turning the pages of a forbidden book, whispering ancient syllables that no master expected him to understand.

Epilogue

The Latin Bible that began it all has never been found. Some believe it turned to ash in 1842; others insist Elizabeth Turner carried it north, or that Jacob buried it somewhere near the river.

But perhaps its physical absence is fitting. The book’s true legacy isn’t in ink or parchment, but in the echo of its words — in a man’s refusal to let knowledge remain the privilege of his oppressor.

Somewhere, between the smoke and silence of that Louisiana night, an enslaved scholar finished his translation and stepped into history’s blind spot — walking not away from the fire, but through it.

And with every line he rendered into English, he rewrote the meaning of freedom itself.

News

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country | HO!!!!

The Widow Paid $1 for Ugliest Male Slave at Auction He Became the Most Desired Man in the Country |…

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!!

The Cook Slave Who Poisoned an Entire Family on a Wedding Day — A Sweet, Macabre Revenge | HO!! The…

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!!

The Enslaved Woman Who Cursed Her Master to D3ath and Freed 800+: Harriet Tubman’s Dark Truth | HO!! History remembers…

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!!

The Giant Slave Science Couldn’t Explain | HO!! Whispers from the Harbor In the winter of 1843, Savannah’s narrow streets…

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO

The Merchant’s Widow Mocked the Idea of Love, Until It Came Wearing Chains | HO A Town Buried in Snow…

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO

The Master Who Made Gladiators Out of Slaves: One Night They Made Him Their Final Opponent | HO Beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load